Common Markets: Leadenhall Court LCT84-6

Gustav Milne

Running up that Hill

Pretend you'd crossed London Bridge in the late 2nd century and were heading north up the main road to the crest of Cornhill.

The skyline was dominated by the  monumental Basilica and Forum (town hall & market), the largest such complex in the country. Its massive scale demanded your attention: it proved that Londinium was the most important town in the province, and don't you forget it. But forget it you must: the whole lot was deliberately demolished in the Roman period long before the entire settlement was abandoned. This was just one of the startling results of the archaeological project at Leadenhall Court in 1984-6, funded by Legal & General Assurance Company, English Heritage and the City of London Archaeological Trust. The excavations incorporated three open areas and fifteen trenches dug in the basements of more- or-less standing buildings. And there were other surprises too, such as evidence of the large medieval Leadenhall Market building, supposedly demolished in the late 18th-century.

monumental Basilica and Forum (town hall & market), the largest such complex in the country. Its massive scale demanded your attention: it proved that Londinium was the most important town in the province, and don't you forget it. But forget it you must: the whole lot was deliberately demolished in the Roman period long before the entire settlement was abandoned. This was just one of the startling results of the archaeological project at Leadenhall Court in 1984-6, funded by Legal & General Assurance Company, English Heritage and the City of London Archaeological Trust. The excavations incorporated three open areas and fifteen trenches dug in the basements of more- or-less standing buildings. And there were other surprises too, such as evidence of the large medieval Leadenhall Market building, supposedly demolished in the late 18th-century.

Déjà vu

The large site at Leadenhall was right next to the eponymous late Victorian market. When it was being built in 1880-1, substantial traces of the underlying Roman basilica were found. These were drawn by Henry Hodge and William Miller, and also painted in full colour, a very detailed record of the Roman remains of revealed there. One arcade base uncovered is still preserved in situ in the basement of a 21st-century hairdresser's: a remarkable initiative, given that the Ancient Monuments Protection Act wasn't given royal assent until 1882. There was therefore no doubt that the neighbouring site where we were to be based had considerable archaeological potential, and so it proved. For the final report, it was possible to incorporate those detailed Victorian observations seamlessly into the 20th-century report. Not for the first or last time, modern excavators were working with materials excavated or recorded by a previous generation of curious archaeologists.

I'd come up in the world by the time I got to Leadenhall: I now had a bicycle. This meant getting to work was a lot faster, if the potholes and juggernauts in the City Road didn't kill you first.  But it was a pleasure to be working in the heart of City right next to the atmospheric 19th-century glazed market. It was designed by Horace Jones, the inventive City architect who also gave us the market buildings at Billingsgate and Smithfield, as well as Tower Bridge, of course. Leadenhall Market gets a name check in Dickens' A Christmas Carol and appeared in films such as Harry Potter's Philosopher's Stone and an Erasure video. Back in 1984, shops included an everyday supermarket (useful for archaeologists) an ironmongers (useful for archaeologists) and the New Moon pub (useful for archaeologists).

But it was a pleasure to be working in the heart of City right next to the atmospheric 19th-century glazed market. It was designed by Horace Jones, the inventive City architect who also gave us the market buildings at Billingsgate and Smithfield, as well as Tower Bridge, of course. Leadenhall Market gets a name check in Dickens' A Christmas Carol and appeared in films such as Harry Potter's Philosopher's Stone and an Erasure video. Back in 1984, shops included an everyday supermarket (useful for archaeologists) an ironmongers (useful for archaeologists) and the New Moon pub (useful for archaeologists).

But there had been earlier markets on the site, one of which dated to at least the 14th century. Associated with a grand medieval building called the Leaden Hall was a large open courtyard subsequently used as a poultry market in the 14th century. Unlike most City markets, whose stalls were set up on major thoroughfares obstructing traffic, the Leadenhall market was set back from the main road. This more convenient location was acquired by the City for a granary to secure the City's grain supply and to provide facilities for a general market complex, which was finally built in the early 15th century. Leadenhall therefore had quite a history: the City's main Roman market place and town hall, a custom-built medieval market, and the spectacular glazed Victorian market. So what might a modern archaeological project add to this rich mix?

We all stand Together

In line with an increasingly common practice in urban archaeology, we had several  trenches excavated in the enclosed basements of the Metal Exchange buildings while soft-stripping of the higher floors progressed. In other such subterranean sites elsewhere in the City, illumination would often be powered by a diesel generator gently humming nearby in an unventilated corner of the cellar: the basements at Leadenhall, however, enjoyed mains electricity.

trenches excavated in the enclosed basements of the Metal Exchange buildings while soft-stripping of the higher floors progressed. In other such subterranean sites elsewhere in the City, illumination would often be powered by a diesel generator gently humming nearby in an unventilated corner of the cellar: the basements at Leadenhall, however, enjoyed mains electricity.

And for the majority of the extensive external investigations at Leadenhall, unlike several other contemporary projects, we had sole occupancy of the open air site, that is, there were no noisy redevelopment-related works being shared with us here. In fact, our Developers, the Legal & General Assurance Company, actually provided support staff to help with spoil removal, hoists, shelter construction and shoreing as work progressed. We were even allowed to squat in a stripped-out office block on site, with spacious if spartan rooms, amply accommodating the whole team, a finds processing facility, a table-tennis table (where did that come from?) and a Tai chi practice room. We also had a manned site viewing gallery with a handling collection, informed stewards and weekly site tours.

As the supervisor for this project, I was most fortunate in working with one of the very best urban excavation teams in the country. Many went on to enjoy famous futures in archaeology, others to glittering careers in the real world.

As the supervisor for this project, I was most fortunate in working with one of the very best urban excavation teams in the country. Many went on to enjoy famous futures in archaeology, others to glittering careers in the real world.

But basically, their experience, expertise and hard graft sorted it all out, a combination of hard digging, detailed excavation and observant recording. Without that, the complexities of understanding the field records, writing up the records and interpreting the various trench chronologies would not have been practical or even possible. However, with regard to our research agenda, I was somewhat troubled on site by Duncan's constant singing of Sam Cooke's classic "Don't know much about Historee".

And the Walls Came Tumbling Down

Although not the only focus, key questions that the project was designed to answer  related to the new basilica, built to replace an earlier, smaller forum complex. Our work showed that work on this major building began in AD 90 but was beset by problems. These included subsidence, since it had been built over loosely-filled pits and ditches, causing the heavy masonry foundations to settle unevenly impacting on the superstructure. And since there were also fires and redesigns to the plan form, the building programme was a long drawn-out affair, not being completed until the late 2nd century, with yet more modifications after that date. But then, probably in or by the early 4th century, systematic demolition began. It now seems that Londinium survived without a formal Forum complex for the first thirty years of its life, as well as for the last century or more. So maybe the massive Basilica civic centre complex was not quite the prestigious propaganda project that it was intended to be.

related to the new basilica, built to replace an earlier, smaller forum complex. Our work showed that work on this major building began in AD 90 but was beset by problems. These included subsidence, since it had been built over loosely-filled pits and ditches, causing the heavy masonry foundations to settle unevenly impacting on the superstructure. And since there were also fires and redesigns to the plan form, the building programme was a long drawn-out affair, not being completed until the late 2nd century, with yet more modifications after that date. But then, probably in or by the early 4th century, systematic demolition began. It now seems that Londinium survived without a formal Forum complex for the first thirty years of its life, as well as for the last century or more. So maybe the massive Basilica civic centre complex was not quite the prestigious propaganda project that it was intended to be.

We now know that for a considerable proportion of its operative life, parts of the Basilica were unused or undergoing reconstruction or repair. By way of an early 2nd century example, in one of the range of offices, the subsidence was so severe in Room 8 that it was never occupied in the first phase of development. The initial floor level had slumped dramatically; an extensive dump of building material had been laid over it to compensate.

We now know that for a considerable proportion of its operative life, parts of the Basilica were unused or undergoing reconstruction or repair. By way of an early 2nd century example, in one of the range of offices, the subsidence was so severe in Room 8 that it was never occupied in the first phase of development. The initial floor level had slumped dramatically; an extensive dump of building material had been laid over it to compensate.

However, that level was covered by mixed grey silt layers, representing uncompacted refuse accumulations, clear evidence of disuse. Within that deposit, a cluster of tiny bones was observed by the astute excavator, Jane Murray of the Institute of Archaeology. Initially thought to represent a rat's nest, a potentially significant find in the prestigious Basilica, she carefully collected the bones as a discrete group.

But what did the bones really represent? Phillip Armitage and Barbara West identified the partial skeletons of a mole (Talpa europaea) and three field voles  (Microtus agresti), unlikely occupants of a major public building. Also, voles and moles do not cohabitate and both prefer rough open grassland, rather than civic centres. The final interpretation for the assemblage was that the mammal bones represented the pellet of a predatory bird that had regurgitated the undigested parts of their prey on the ground beneath the rafters where it had been roosting. Further research identified a likely culprit: a barn owl. Not only was it able to roost in an inner room of the Basilica, but the pellet lay undisturbed for sufficient length of time for layers of silt to accumulate over it.

(Microtus agresti), unlikely occupants of a major public building. Also, voles and moles do not cohabitate and both prefer rough open grassland, rather than civic centres. The final interpretation for the assemblage was that the mammal bones represented the pellet of a predatory bird that had regurgitated the undigested parts of their prey on the ground beneath the rafters where it had been roosting. Further research identified a likely culprit: a barn owl. Not only was it able to roost in an inner room of the Basilica, but the pellet lay undisturbed for sufficient length of time for layers of silt to accumulate over it.

All this supports the excavators' contention that parts of the Basilica were left unoccupied and that the building programme was intermittent and protracted. It also implies that Londinium's area of intense urban occupation in the 2nd century was limited. This is because the bulk of hunting for these birds is carried out within a few hundred metres of the roost site over rough grassland: however, a hunting area with a 400m radius centred on the Basilica roost was entirely within the later City's boundary, implying much of the land was still under-developed.

To conclude, the form of the civic centre's ambitious plan encapsulated the noble aspirations of the time, but the somewhat sad sequence recorded by archaeologists and eco-archaeologists demonstrated the period's unforgiving realities. And at least somebody knew something about biologee.

Architectural Archaeology

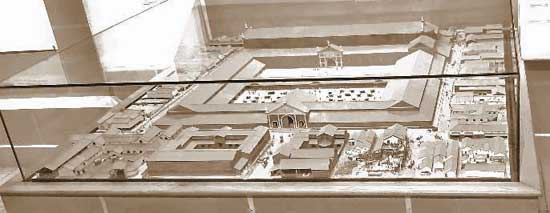

The exposure, excavation and recording of the substantial remains of basilica complex with its nave, aisles, offices and shops was a major component of the team's activities in all of the trenches opened. The evidence collected for the form and dating of foundations, superstructure, flooring, use and disuse was considerable. This was brought together by Trevor Brigham in a magisterial study that incorporated not just the LCT84-6 data and the late 19th century records made during the construction of the glazed market, but also from some 23 other excavations and observations right across the whole Basilica and Forum site, an

archive compiled between 1881 and 1990. From these data, he reconstructed the whole civic centre on paper, a huge achievement. And there was more: he also worked on a huge three-dimensional scale model, which was proudly displayed in the Museum of London's Roman gallery (fingers crossed it resurfaces in the new London Museum).

archive compiled between 1881 and 1990. From these data, he reconstructed the whole civic centre on paper, a huge achievement. And there was more: he also worked on a huge three-dimensional scale model, which was proudly displayed in the Museum of London's Roman gallery (fingers crossed it resurfaces in the new London Museum).

But that was not the only major public building the archaeologists found: in January 1985, archaeologists were stripping off wall plaster in a derelict building in Gracechurch Street, on the eastern side of the LCT84 site. To their amazement, they began to reveal the face of a 15th century wall, surviving from the basement level to the fourth floor, a height of 11m. A truly dramatic discovery in the middle of the much redeveloped City of London: somehow, a substantial fragment of the medieval Leadenhall Market building had survived the Great Fire and the Blitz, even though most of the structure had apparently been long demolished.

But that was not the only major public building the archaeologists found: in January 1985, archaeologists were stripping off wall plaster in a derelict building in Gracechurch Street, on the eastern side of the LCT84 site. To their amazement, they began to reveal the face of a 15th century wall, surviving from the basement level to the fourth floor, a height of 11m. A truly dramatic discovery in the middle of the much redeveloped City of London: somehow, a substantial fragment of the medieval Leadenhall Market building had survived the Great Fire and the Blitz, even though most of the structure had apparently been long demolished.

Next door, excavators on the main site then began dismantling cellar walls, from which nearly 200 moulded stones reused from the demolished medieval market building were recovered. These remarkable artefacts were carefully recorded by Mark Samuel, who also brought together an archive of sketches and elevations, as well as a detailed plans of the market surveyed in 1676 and in 1794, on the very eve of the demolition of the north range.

Working with the plan of subsurface foundations recorded on site related to the surviving 17th and 18th century surveys, he accurately reproduced the full ground plan. Study of the elevations of the surviving wall fragment clearly showed the actual heights of the ground, first and second floors, and the 177 moulded stones provided architectural details and dimensions of doors, windows, arcading and even the spiral stairs in the corner towers. On paper, he stunningly recreated the unique and remarkable civic market building designed by John Croxtone in the early 15th century, 300 years after its demolition. When all is said and done, archaeological research is more than just producing grey literature reports: it's very much a three-dimensional study of a three-dimensional City.

Working with the plan of subsurface foundations recorded on site related to the surviving 17th and 18th century surveys, he accurately reproduced the full ground plan. Study of the elevations of the surviving wall fragment clearly showed the actual heights of the ground, first and second floors, and the 177 moulded stones provided architectural details and dimensions of doors, windows, arcading and even the spiral stairs in the corner towers. On paper, he stunningly recreated the unique and remarkable civic market building designed by John Croxtone in the early 15th century, 300 years after its demolition. When all is said and done, archaeological research is more than just producing grey literature reports: it's very much a three-dimensional study of a three-dimensional City.

But those there-dimensions didn't last long at Leadenhall once the archaeologists moved out and the ground reduction programme moved in. Two Poclain 190 excavators working in tandem removed the remaining archaeological strata into a fleet of lorries, a process known as "Muck Away". In response, the archaeologists mounted a "watching brief": they watched all too briefly as the basilica disappeared.

We were still working on the LCT site records in October 1986. The last few years had seen the discovery of mid Saxon Lundenwic in Covent Garden and the excavation of a huge medieval Black Death cemetery near the Tower, both by our sister unit, the Department of Greater London Archaeology. These were big projects and big sites, while Leadenhall Court was one of the largest most complex sites in the City itself: were we looking at the end of an era for such schemes? Archaeological sites are a very finite resource, so we could be forgiven for assuming that the majority of major sites worth digging had been dug, not least because so many pre-WW2 buildings were now safely locked inside Conservation Areas.

We were still working on the LCT site records in October 1986. The last few years had seen the discovery of mid Saxon Lundenwic in Covent Garden and the excavation of a huge medieval Black Death cemetery near the Tower, both by our sister unit, the Department of Greater London Archaeology. These were big projects and big sites, while Leadenhall Court was one of the largest most complex sites in the City itself: were we looking at the end of an era for such schemes? Archaeological sites are a very finite resource, so we could be forgiven for assuming that the majority of major sites worth digging had been dug, not least because so many pre-WW2 buildings were now safely locked inside Conservation Areas.

But then, on Monday 26th October, everything changed. With the so called "Big Bang" the financial markets in the City were suddenly deregulated. This single act, among other issues, introduced electronic trading to the markets, abolished minimum fixed commissions on trading stocks and shares and allowed foreign firms to own UK brokers, all of which acted as a strong magnet for international bankers to work here.

And the new companies needed new, improved offices, and that meant a surge in new developments in the City. And that meant a surge in new archaeological sites to investigate. So 1986 wasn't the beginning of the end: it was, for some, the beginning of a new beginning. But that's another story.

The Leadenhall Court project was generously funded by Legal & General Assurance Company, English Heritage and the City of London Archaeological Trust,.

{Backbutton}

Comments powered by CComment