A memorable trip to Libya (and back) in 1979

Peter James

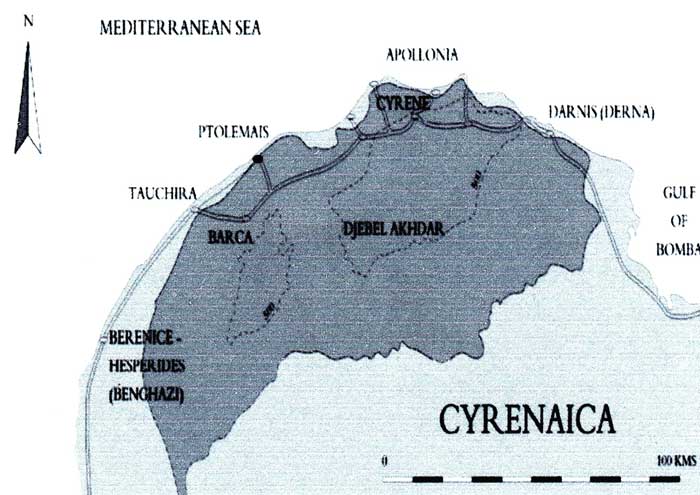

Ptolemais was one of the five major cities of the ‘Pentapolis’ in Cyrenaica, the coastal region of eastern Libya, comprising Cyrene, Apollonia, Taucheira (Tocra), Euhesperides (Benghazi) and Ptolemais.

The ancient city lies on the Mediterranean coast about 110km north east of Benghazi, and occupies a narrow space between the sea and the lower spurs of the Jebel el-Akhdar (Green Mountain) range, c.2km to the south.

Map of Cyrenaican Pentapolis

Map of Cyrenaican Pentapolis

Ptolemais began as a Greek settlement founded in the 7th century BC and functioned as a port for the town of Barca, 24 km inland. The city later controlled the line of the Roman road to Cyrene. By the mid 3rd century BC the settlement was replaced by a new city called Ptolemais, founded by Ptolemy III (246-221 BC), one of the dynasty of Macedonian rulers of Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC.

The city plan was based on the latest trends in Hellenistic urban planning. Extensive defensive walls enclosed an area of over 200 hectares. The city was laid out on grid plan with major streets running north-south and a main east-west avenue (the Street of the Monuments) that eventually received a triumphal arch dedicated to Constantine the Great in 311-312 AD. The large city blocks (insulae) measured 100 by 500 Ptolemaic feet (36.5 m by 182.5 m).

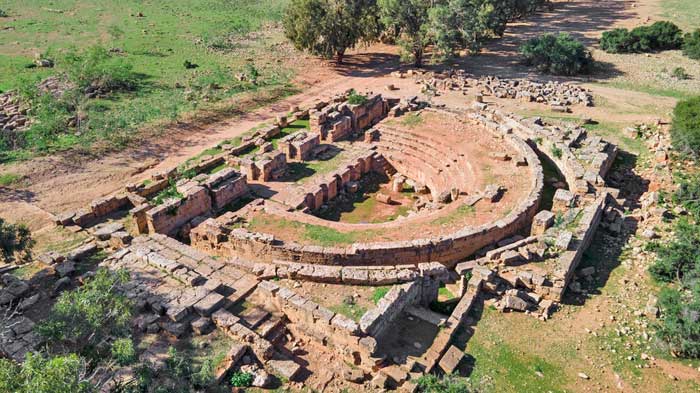

Some of the most remarkable features of Ptolemais are the several well preserved insulae containing large peristyle houses that were built in the Hellenistic period and refurbished and enlarged in the Late Roman period. These houses were richly decorated with frescoes, mosaic floors and sometimes private baths. The city also had several public Roman and Byzantine baths, an amphitheatre, a hippodrome, and three theatres.

Ptolemais: the 'Palace of the Pillars' (remodelled in 1st century AD)

Ptolemais: the 'Palace of the Pillars' (remodelled in 1st century AD)

Ptolemais: the 'Mausoleum' (1st century BC)

Ptolemais: the 'Mausoleum' (1st century BC)

Ptolemais: Town house ruins

Ptolemais: Town house ruins  Ptolemais: 'The Odeon' theatre

Ptolemais: 'The Odeon' theatre

Ptolemais: the 'Fortress Church' (6th centuryAD)

Ptolemais: the 'Fortress Church' (6th centuryAD)

The site lacked nearby water sources, so its water supply depended on cisterns fed by an aqueduct that carried water from a spring about 8 km east of the city. The size and number of the city’s public cisterns and reservoirs are impressive. One group of seventeen vaulted cisterns under the Roman “Square of the Cisterns” had a capacity of 7,000,000 litres.

Such energy devoted to ensuring an adequate water supply underscores the importance of supporting a population large enough to maintain a strategic harbour. The harbour was on the eastern side of the city and aligned with the main avenue. An ancient lighthouse was positioned on a promontory near the harbour, underneath the present one.

Ptolemais continued to flourish in the Roman period, achieving a yet higher prominence in the early fourth century AD, when the city became the capital of the newly created province of Libya Superior/Pentapolis under Diocletian. In the Early Christian period Ptolemais was also the seat of an influential Christian bishopric. Subsequently the city decayed and Apollonia (Sozusa) supplanted it as capital. However there is plenty of evidence for continuing occupation of the site after the Islamic conquest of North Africa in the 7th century AD. Written sources refer to it as an anchorage and trading-post until at least 14th century. However 18th and 19th century European visitors to the standing ruins described the site as being abandoned.

Systematic excavations began in the twentieth century, first by Italian and subsequently by American and British teams.

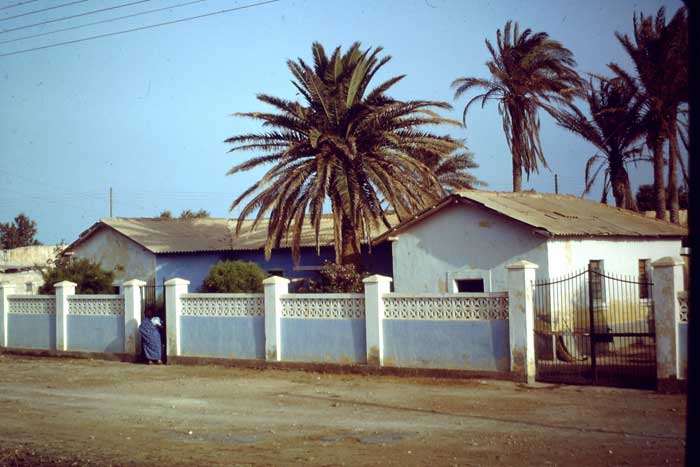

During the Italian occupation in the early 20th century a small colonial town, Tolmeita, was built adjacent to the ancient harbour area. There is a small museum in the town, created in a former storehouse in the 1960’s, that houses a rich and varied collection.

Tolmeita (or Ptolemais) Museum

Tolmeita (or Ptolemais) Museum

Located on the edge of Tolmeita, just a short walk from the ancient remains, is the house that provided accommodation for the British teams excavating the site, including myself and the late Prince Chitwood (1949 - 2005) for a few weeks in July and early August 1979.

The dig house in Tolmeita

The dig house in Tolmeita

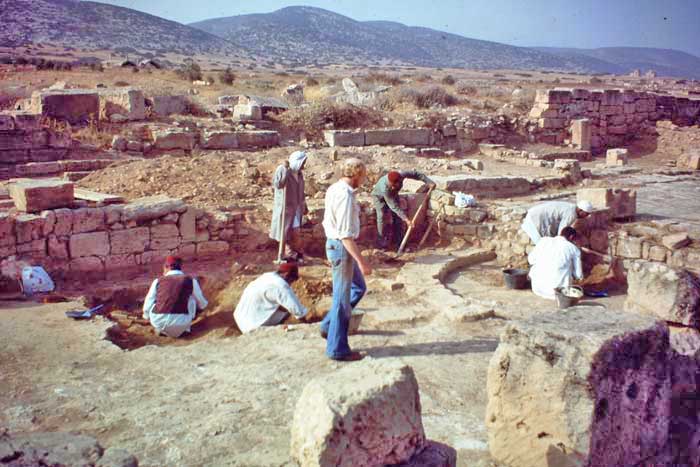

Richard Goodchild excavated at Ptolemais in the 1960’s and his work was followed up in three excavations in the 1970’s: in ’71, directed by Lady Wheeler, and in ‘78 and ’79, directed by John Ward-Perkins with co-director John Little.

Ptolemais: the Street of the Monuments

Ptolemais: the Street of the Monuments

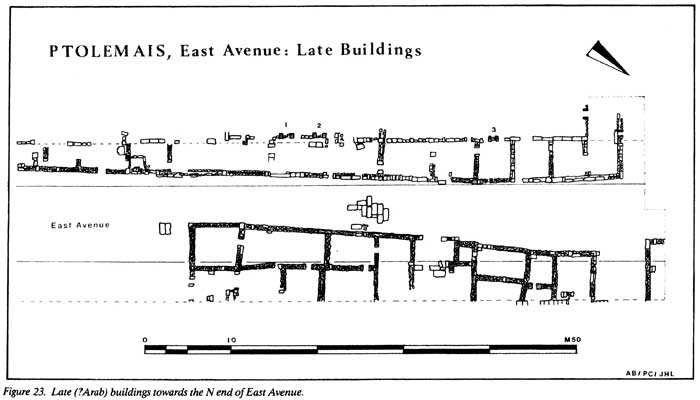

This work was funded by the Society for Libyan Studies and the British Council and focused on a part of the city christened the ‘North East Quadrant’ lying at the intersection of two main streets, the East Avenue and the Street of Monuments. This archaeologically-rich area included three Hellenistic town houses and tells a complex story of building, rebuilding, adaptation and changes of use over an extended period, from the Hellenistic era in the 3rd century BC to the Islamic invasion of the 7th century AD and beyond.

Unfortunately, in 1979 Ward-Perkins and his small team were not able to complete all their objectives before they had to leave to fulfil work commitments elsewhere. At that time I was living in Sheffield and working for John Little, who was the County Archaeologist for South Yorkshire County Council. As the excavations in Ptolemais were drawing to a close John contacted me and asked me to go out to Libya to finish off some elements of the work, and generally tie up loose ends. He also asked me find a suitably qualified person to help. Prince had recently finished digging a site with me, for the county council, and was available, willing and - unlike me - had previous experience of working in north Africa (in Carthage) so he was promptly hired.

I flew alone to Benghazi and was met at the airport by John Little, who accompanied me on the long taxi ride to Tolmeita. Prince arrived the next day, if I remember correctly, and John only had a small amount of time in which to brief us before he had to return to England. My initial impressions on arriving in Benghazi were of a place very different from any I had visited before. The first thing to hit me on stepping off the plane at the airport was the heat, which was of an intensity I had never encountered before, but there was much else to take in: palm trees, mosques, the clothes, the currency - and camels too! I had never seen one outside of a zoo, but on our taxi ride from the airport I vividly remember being overtaken by a pick-up truck with a camel sitting in the back, head towering above the roof of the truck and looking disdainfully at everything around him. And if I needed any more evidence that I was somewhere very different there was the presence, throughout my stay in Libya, of the noise from above of countless fly-overs by Colonel Gaddafi's Russian-made MIG fighters and helicopter gunships.

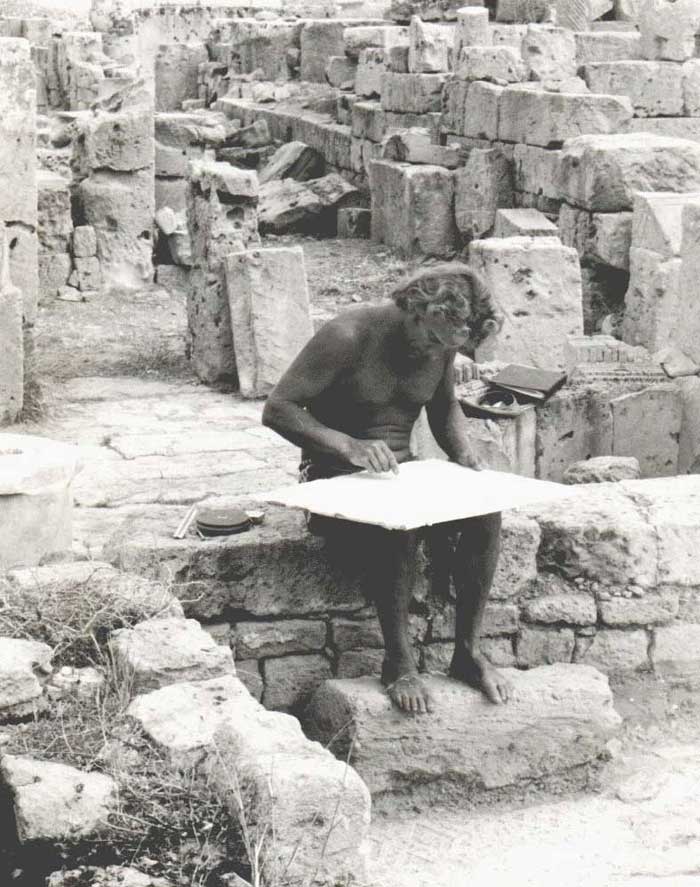

Surveying with John Little

Surveying with John Little

My memories of the work Prince and I did are a little hazy now, but our main tasks were to complete the removal of scrub and topsoil (or wind-blown sand) in a few specified rooms, and then record the underlying (i.e. latest surviving) floors, and complete the drawings of certain features. These included elements of the latest periods of construction, rather roughly built edifices when compared with the classical architecture of the earlier periods, some of which overlay parts of the Hellenistic/Roman East Avenue. These latest buildings dated from the earliest times of the Islamic period of occupation in north Africa.

Ptolemais: a busy morning on site

Ptolemais: a busy morning on site

John Little wrote in an interim report in 1986 that “The late phases of reconstruction and habitation in this quarter of Ptolemais were of a type which have been dismissed all too often by classical archaeologists as ‘squatter occupation’ but Ward-Perkins himself was quick to realise the unique importance of these structures. The chance preservation of so much of this evidence in this area affords us an insight into the true complexity of some of these later buildings and demonstrates the absurdity of terms such as ‘squatter occupation’, with all the implicit assumptions which go with them.”

Ptolemais: the East Avenue looking north-west, with Tolmeita in the back ground

Ptolemais: the East Avenue looking north-west, with Tolmeita in the back ground

Ptolemais: the East Avenue looking south, towards the Jebel el-Akhdar range

Ptolemais: the East Avenue looking south, towards the Jebel el-Akhdar range

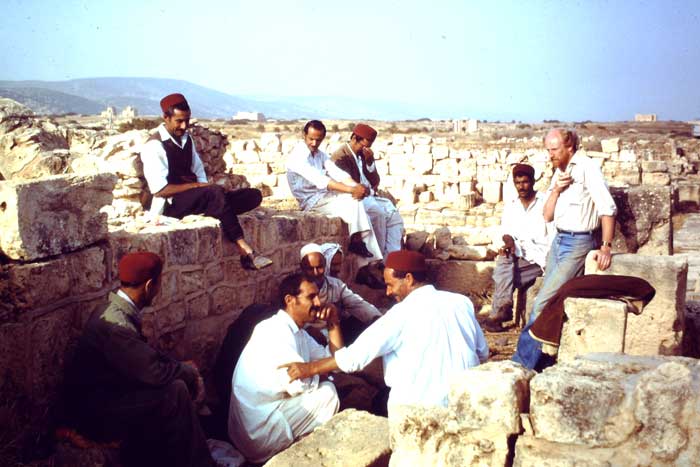

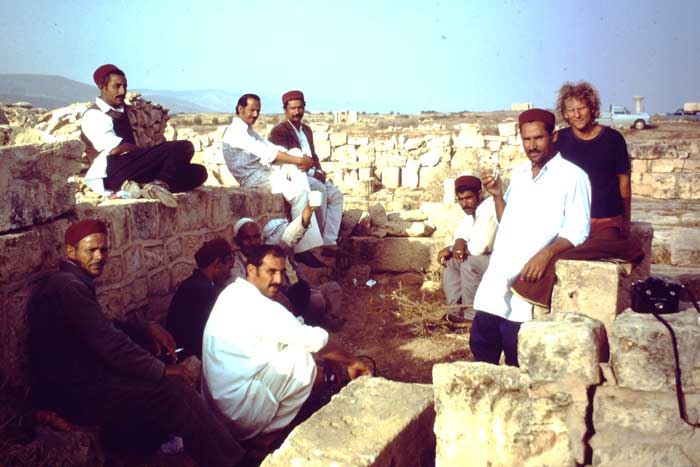

On site the workforce comprised Prince, myself and a team of about a dozen local workers. We started work at 6am and had a break at 8.30, when breakfast consisted of very strong, very sweet mint tea brewed in an enormous kettle over an open fire, and omelettes that were delivered every morning in a police car, courtesy of a local PC who was the brother of one of our workers. Work stopped at 3 in the afternoon, when the heat got to be almost unbearable, although Prince and I often went back on site in the cooler air of the evenings to do more recording, or to plan our next moves. (Let’s face it, the night life there wasn’t up to much!)

Ptolemais: the mid morning breakfast

Ptolemais: the mid morning breakfast

There are some events from that time that have stuck in my mind, some vivid, others less so. What follows are my stand-out memories.

An unusual storm: I remember Prince and I standing on the roof of our ‘dig house’ one night watching in awe a ‘dry lightning’ electrical storm flickering over the hills of the Jebel al Akhdar, a phenomenon I had not seen before and have not seen since.

A descent into the unknown: We decided at some stage that it would be interesting to explore the famed underground cisterns so, armed with candles and a rope ladder found in the tool store, we removed a capping stone and noted that there was a drop of about 2.5 metres to the floor below. Having made the ladder secure we tossed a coin to decide who was to go down first, and to my great relief Prince lost. So down he went, but seconds later I heard him shouted “F***, there’s a snake!!” He came back up the ladder at a speed I wouldn’t have thought possible, yelled “Give me a shovel” and, thus armed, went down again and swiftly despatched the unfortunate creature. The candles were our only source of light, apart from a cheap little torch, but they allowed to see that the cistern was rock-cut, about 2 meters high, from the ‘floor’ of accumulated debris to the roof, and about 3.5 metres wide. However, candle light didn’t make for good photographs - this was the best of my efforts!

Ptolemais: a water cistern

Ptolemais: a water cistern

Fauna: Apart from the amazing archaeology the site was remarkable for its wild life too – snakes, scorpions, birds (it was a clearly a great hunting ground for Little Owls and raptors) and crickets, many of them with a 15 centimetre wing span that would jump to head height so we had to duck to avoid them! On a number of occasions a scorpion would be spotted while we were working and a shout would go up, resulting in the whole workforce joining the hunt, taking great delight in chasing it and trying to hit it with a shovel. And then there were the cockroaches.... Prince and I shared a bedroom and every night, as soon as we switched off the light, the clicking and rustling noises would start up. Putting the light back on would reveal an army of cockroaches all over the floor, but now rushing back to their hiding places. Prince’s solution was to go to bed with his work boots on. He would wait in the dark until the noise reached its crescendo and then switch on the light as he jumped out of bed and did his ‘roach dance’, stamping on them. He was never going to get them all, of course, but he created enough carnage to leave a sticky (but crunchy) layer on the floor every night...which it was my job to clear up every morning!

A little Owl at his lookout

A little Owl at his lookout

Site visitors, a party and an embarassing incident: Tourism was non-existent in Libya at that time so we had very few visitors to the site, apart from some Brits and Americans, some with their families, who worked for the oil industry and were living in an enclosed compound a couple of miles from the site. Prince and I were invited to a party there one night and although Libya was supposedly a ‘dry’ country the amount of alcohol flowing that evening was unbelievable!

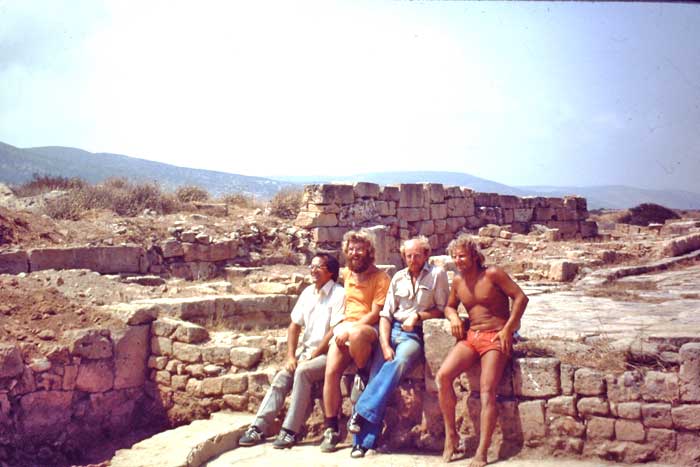

Our first site visitors

Our first site visitors

A group up of these expats visited us for a site tour one day, and while giving them an introductory talk I became aware of something crawling over my ankle, under my trouser leg. I tried to keep calm and stoically kept on talking, telling myself that it was probably something small and harmless, but as it moved up my leg, bit by bit, I found it increasingly difficult to concentrate as I became more and more convinced that it must be a scorpion. But when it reached a point about 15 centimetres above my knee I could hold out no longer. I stopped talking, said “Sorry folks but..” and dropped my trousers to hunt for the culprit - at the same time all too aware of what could happen if I frightened it! Happily my uninvited visitor did turn out to be a small, harmless cricket. I have never forgotten, though, the odd mixture of terror and embarrassment I felt at that moment. (I have a suspicion that what our tour group took away from their visit was not a deep understanding of the archaeology and history of the site but a memory of me becoming more and more alarmed as the creepy-crawly climbed up my leg and then dropping my Levis to display my lilywhite legs.)

A grand day out: The very helpful and hospitable Director of Antiquities at Ptolemais, Essayed Abdussalam Bazama, gave up a day of his time to take us on a tour of the area, including visits to the remains of two other cities of the Pentapolis, Apollonia and Cyrene.

Apollonia: columns of the Early Byzantine Central Basilica (with Director of Antquites Essayed for Ptolemais, Abdussalam, ans assistant

Apollonia: columns of the Early Byzantine Central Basilica (with Director of Antquites Essayed for Ptolemais, Abdussalam, ans assistant

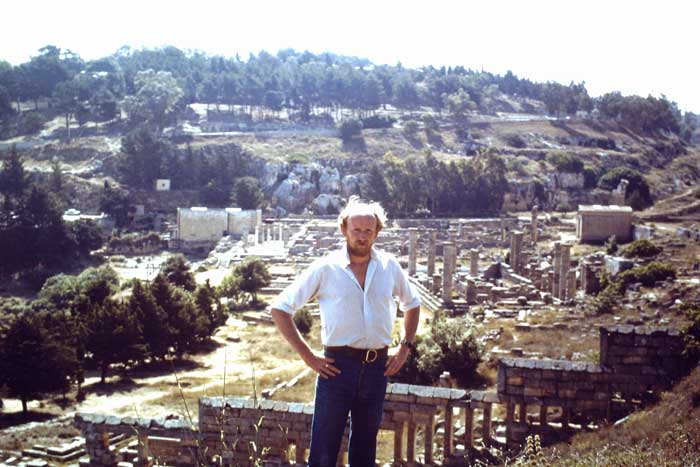

Cyrene: the 6th century BC Temple of Zeus under construction

Cyrene: the 6th century BC Temple of Zeus under construction

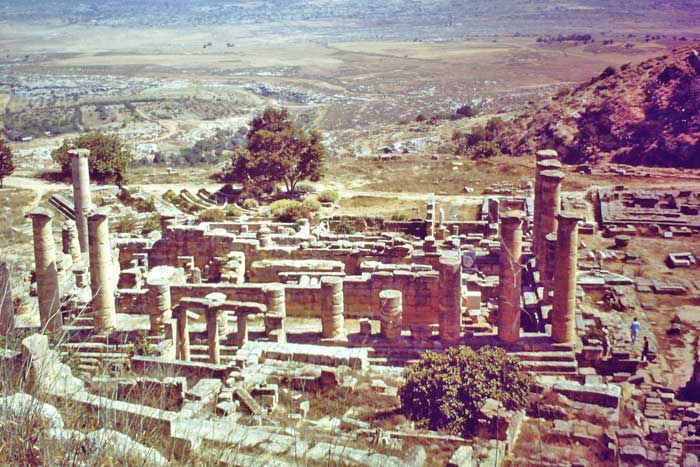

Cyrene: overview of the 6th century BC Sanctuary of Apollo

Cyrene: overview of the 6th century BC Sanctuary of Apollo

A change of plan: A week or so before Prince and I were due to return home to the UK we received a message from John Little asking us to change our travel plans. We were asked to fly from Benghazi to Tunis, where a Land Rover was laid up and waiting to be delivered back to Newcastle upon Tyne. The vehicle had broken down when an archaeological expedition to the Fezzan in southern Libya (also on behalf of the Libyan Society, and led by Charles Daniels of Newcastle University) was returning to Tunis to catch the ferry to Marseilles and then travel on to the UK. The repair was going to take a while so the survey team decided to fly home without it. While the Land Rover was being repaired and our papers, tickets etc, were sorted out Prince and I were to stay at the HQ of an American team digging at Carthage.

My last memory of Libya is of waiting for our flight in the departure lounge of Benghazi airport. The ‘entertainment’ being broadcast over the several screens dotted around the concourse was a political rally featuring a long rabble-rousing speech by Colonel Gaddafi. The most remarkable thing about it, to us, was that a large proportion of his audience in this oil-rich nation were what appeared to be tribesmen, on horseback, wearing traditional dress and bandoliers, and brandishing rather old-looking rifles and roaring their support, every man evidently very fired up by their hero.

Our stay in Carthage was both enjoyable and memorable. In particular I remember visiting the remains of the Punic harbour and the ‘Tophet’ (infant cemetery), the souk in Tunis, having a meal (and many many beers) with some of the locals Prince knew from his previous visit, and the hospitality of the American archaeologists working out there (including Patrice Panella, who later married Angus Stephenson). I remember also that we also received first class administrative support from a wonderful local lady called Genevieve, who (I think) worked for the British Council. It was she who expertly arranged our accommodation, the transfer of money for our expenses, and our tickets and permits for travel.

Carthage: with Patrice Panella and colleagues at the American dig house

Carthage: with Patrice Panella and colleagues at the American dig house

Carthage: the Punic harbour

Carthage: the Punic harbour

After five or six days in Carthage we got the call to come and collect the (now repaired) Land Rover. It was with heavy hearts that we prepared for our long journey home and then said goodbye to the people who had been so helpful and hospitable to us. Our days in Carthage had been ones of leisure, in very good company. Driving from Marseilles to Newcastle upon Tyne in as short a time as was safely possible felt like it was going to be a challenge. Admittedly the first leg wasn’t a hardship; the Tunis to Marseilles car ferry was a large ship, luxurious (by our standards anyway - it even had a swimming pool) and the crossing, in calm and balmy weather, took two days. When we docked in Marseilles we got a scare when the Land Rover refused to start and had to be towed off the ship, but on dry land it miraculously woke up and after that gave us no more trouble.

We drove for three to four hours every day, with short stops only for fuel (for us and for the vehicle), overnight sleeps, and for some photo opportunities we felt it would be a shame to miss; at the Pont du Gard, the Palace of Versailles and the Eiffel Tower.

The Pont du Gard

The Pont du Gard

A long wheel-base Land Rover loaded to the roof with all the kit needed for a month-long recce in the wadis of the Fezzan was never going to be the speediest mode of transport so it took us the best part of 5 days to cover the c.1000km to Calais. On the sixth day we crossed to Dover and then headed for Sheffield, to drop Prince off and for me to get some clean clothes and spend a night in my own bed. The next day I drove the final leg, to deliver the vehicle to Charles Daniels at Newcastle University, who needed it for his annual 2nd year archaeology students’ training dig at Housesteads fort (which, incidentally, was to be my next gig, after a just few days back in the office in Sheffield.)

Home again - the Land Rover parked outside my flat in Sheffield

Home again - the Land Rover parked outside my flat in Sheffield

So ended our big adventure in north Africa, a trip never to be forgotten and an opportunity I feel very grateful to have been given. I can’t say that my memory is infallible, but I have tried to recount these events this story as accurately as I can. I do wish, though, that Prince could have helped me to write it. I have no doubt he would have been able to add, improve or correct some details, to good effect. He is missed in many ways. I will never forget his energy, his zest for life and his ‘can do’ attitude. He was a good companion - if an infuriating one at times! I have tried to trace John Little, hoping to have his input, but without success. (If you happen to see this John then do get in touch, via Digging London.) For the details of the archaeological work Prince and I assisted with at Ptolemais I have had to rely on two interim reports:

Excavations in the North-East Quadrant. 1st Interim Report by J. H. Little in The Society for Libyan Studies 11th Annual Report (1979-80)

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263718900008530 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Town Houses at Ptolemais, Cyrenaica: A Summary Report of Survey and Excavation Work in 1971,1978-1979 by the late J. B. Ward-Perkins, J. H. Little and D. J. Mattingly (with a contribution by S. C. Gibson) in Libyan Studies 17 (1986)

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263718900007093 Published online by Cambridge University Press

The map of the Cyrenaican Pentapolis is reproduced from: The Harbour at Ptolemais: Hellenistic City of the Libyan Pentapolis: R.A. Yorke & D.P.Davidson: Survey of the harbour at Ptolemais in International Journal of Nautical Achaeology 46 (1), March 2017

Pete James, January 2023

Pete James, January 2023

Comments powered by CComment