Trondheim

Tom Chilton

April 1975

I was scratching away on the GPO site next to St Pauls. It wasn't a great site - modern intrusions had removed a lot of the archaeological deposits and it wasn't as much fun as Seal House.

I'd come down from Scotland as John Schofield's protégé, and worked down a deep dark smelly trench with some wonderful people - Graham Troillet, Paul Herbert and the most exotic person I had ever met - Richard Burton - Chunkarella!!!

I had a decision to make. It turned out to be a decision that took me away from the UK and eventually led me here, to a Baroque town 30 miles up the Danube from Budapest.

When I first came down from Scotland, in the summer of 1974, I lived on a houseboat in Chelsea, now I was living in a squat off the Holloway Road. In the winter of '74. London was dirty, wet and IRA bombs were going off every couple of weeks.

The DUA was handing out permanent contracts and I was on the list, but Howard Murray (conservator and fellow-Scot) encouraged me to apply for a job on a dig in Trondheim, Norway. Should I stay or should I go? I was only 23 - I went.

On May 16, 1975 I boarded a Fred Olsen ferry in Newcastle bound for Bergen. I was travelling third-class (formerly known as steerage). Among my fellow passengers were a couple who were smuggling cannabis into Norway. We sat in a saloon in the bowels of the boat, passing a joint back and forth and playing chess. We abandoned the game when we noticed that both of my bishops were on the same coloured squares.

I realised that no-one was going to stop me venturing up into the classier part of the ship. There was a bar, a dancefloor, a pianist, and a lissome blonde from London. It turned out she too was heading for the Trondheim dig. Fuelled by duty free and lust, we danced into the night as the ferry chugged over the North Sea. In the small hours, clinging together in an empire built for two, we asked the pianist to play the theme from

In the morning, she took the train to Trondheim via Oslo, while I sailed up the coast with the Hurtigruten

"Hurtigruten" means "Express Route" but the voyage to Trondheim took 36 hours with stops at the pretty but fishy-smelling ports of Ålesund and Kristiansund.

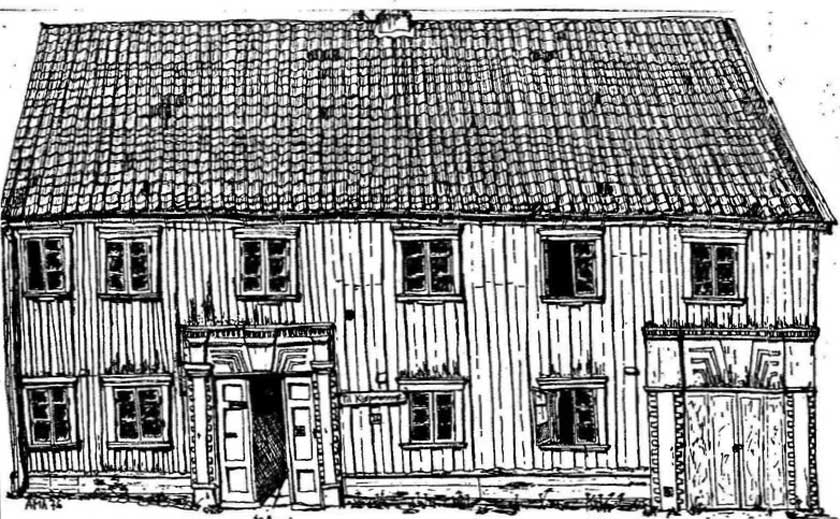

Next day, 30 diggers assembled to be briefed by director Clifford Long in the courtyard of number 26 Kjøpmannsgata, the house in which we were all going to live for the next few weeks. Number 26, which also housed the office and finds department, was a massive wooden town house built in 1814 as a girls' school. It was right next to the site, it was the scene of much festivity, and it was haunted.

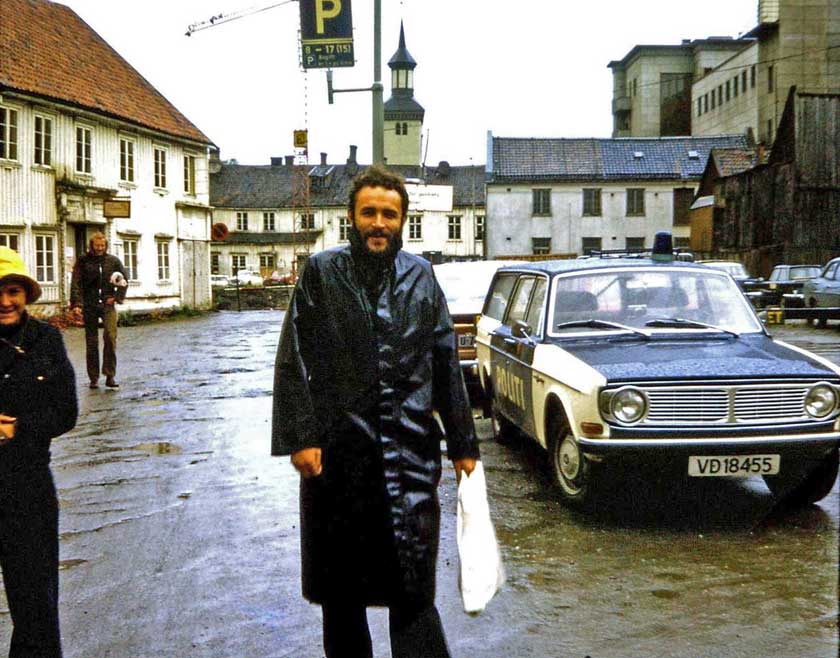

Cliff was camp and funny but had a tart side to him. He introduced the two deputy directors - Ian Reed from Hartlepool, and Erik Jondell from Sweden. Ian became a medieval pottery expert and still lives in Trondheim. Erik became a museum director and now spends his summers touring Norway on his bright red Triumph motorbike.

Ian and Cliff in Bodo's house

Ian and Cliff in Bodo's house

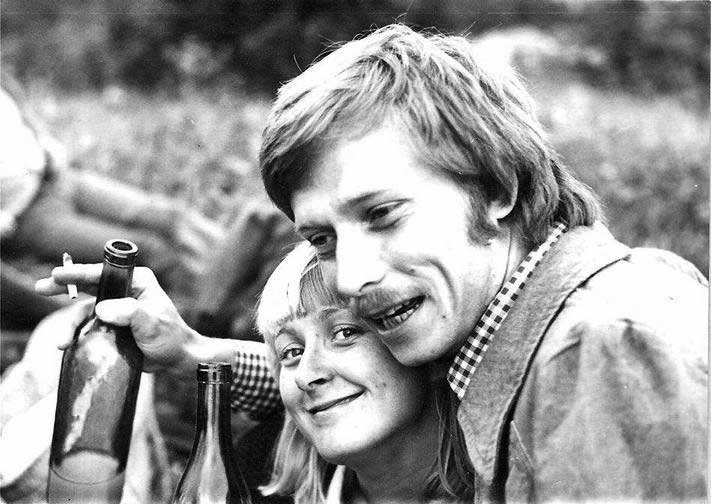

Erik (in uncharacteristic pose) with Inger Sofia (Fifi)

Erik (in uncharacteristic pose) with Inger Sofia (Fifi)

I looked around at my fellow diggers - half were Scands - mostly hairy people wearing clogs, striped peasant shirts and PLO scarves. Most of the remainder were Brits, but there were also a fair number of Irish, two feisty American women (in finds), a chic Frenchwoman who spent a lot of time in Kabul, and a very jolly Bavarian called Heri, who got rich in the winter by being on call to drive snowploughs in West Berlin.

Cliff introduced us to the rules and rotas of communal living - which worked well except for when Scand cleaning teams washed out the Brits' chip pan. He warned us not to convert Norwegian prices into pounds - still good advice for anyone visiting Norway. In 1975, a beer in a bar cost 14 kroner (about £1.20) as compared to 32p in the UK.

Martin Howe outside nr 26 with the site behind. Fire station top right

Martin Howe outside nr 26 with the site behind. Fire station top right

We were led to the tool store. Here a surprise awaited - there were no picks or mattocks and only a few unwieldy shovels. Instead there were fylhakke (a bird-headed tool for hacking) krafsa (a giant crescent-shaped hoe) and krafsebrett, the two-handled tray that is the Robin to the krefsa's Batman.

Luckily we Brits had all brought our trusty WHS trowels, some almost totally worn down, status symbols but virtually useless. We prevailed upon Ian Reed to buy some nimbler shovels and he procured some light-headed long-shafted shovels, the best I ever used. These allowed the ace digger to demonstrate the essential art of wheeching soil into a distant wheelbarrow with minimal splatter.

In fact we didn't need to use wheelbarrows that much because we had a crane. A tower crane. A real one. And we could operate it ourselves, or at least one person could, usually Dick Grove. Several skips were placed around the site. When these were full, the crane was summoned and the spoil removed. It was very convenient and no-one was decapitated. It was also used to take overhead photos of the site, although only after checking that no safety inspectors were lurking nearby.

The site, excavated prior to the construction of a new library, was a wonderful place to dig. There were very few later intrusions and organic materials survived even though the site was not waterlogged. The medieval houses and streets were made entirely of wood and most of the layers we excavated were partly or wholly comprised of treflis (woodchip). Around 1.5 metres of kulturlag (archaeological deposits) had accumulated between the city's foundation in 997 and the mid 14th century when Norway was ravaged by the Black Death.

There were two types of construction. The most common (laft) had interlocking corners like an American log cabin. The other (skifteswerk) had corner posts with grooves up the side, into which the walls were slotted

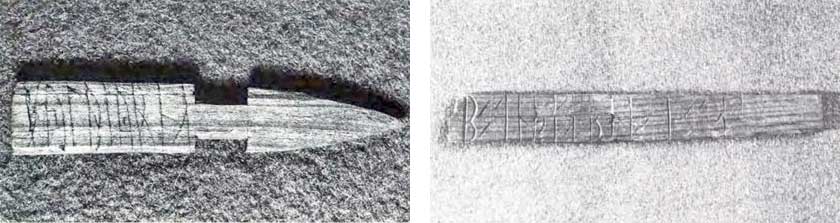

The finds were exceptional. We found bits of 1,832 shoes. The star finds were bone combs, decorated wooden objects and rune pins. There were bowls of water on site where likely-looking bits of wood could be gently washed. If you were very lucky, you turned the stick to catch the light and a message from 800 years ago appeared. The inscription was often merely futhark (the runic alphabet) but some, like the arrow-shaped piece below, contained a name. These were probably used to mark the ownership of trade goods - bales of pelts for example. Very occasionally the runes seem to have had a magic meaning. The inscription on the rune pin below right can be read both forwards and backwards.

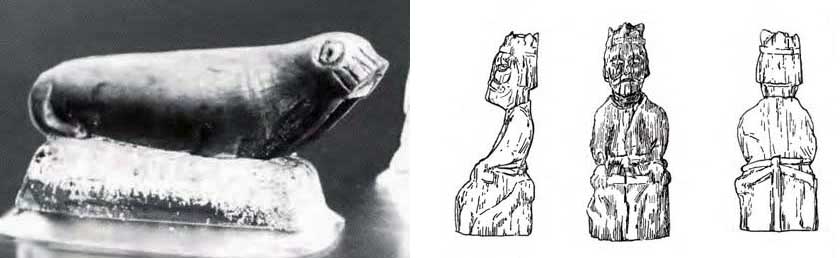

Two finds became symbols of the excavations in Trondheim. A cute walrus carved from walrus ivory and a wooden king from a chess set.

Apart from a freak snowstorm, the weather was glorious in the summer of '75. And it never got dark. During the twilight hours of 10pm to 2am, the wind dropped and time held its breath. It is a magic time - a midsummer night's dreamworld. If you were out late, the sun came up and there seemed little point in bothering to sleep. After a few days, I was in a daze.

It rains quite a lot in Trondheim though, especially towards the end of the digging season in September. This was no problem for the Norwegians, who had been issued with a complete set of Helly Hansen rainwear at birth, but not so good for we Brits with our army surplus gear, and even worse for Dave Fine, who wore a pin-striped three-piece suit throughout his stay.

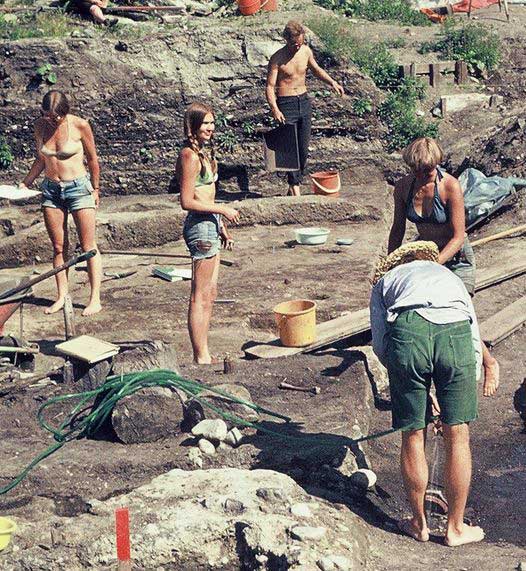

We never wore any safety clothing in the early days. In the long hot summer of 1976, we hardly wore any clothing, or footwear, whatsoever.

The lone Brit, Jonathan Wordsworth, still able to concentrate on his plumb bob. The topless Leif Zerpe is holding a krafsebrett.

The lone Brit, Jonathan Wordsworth, still able to concentrate on his plumb bob. The topless Leif Zerpe is holding a krafsebrett.

We started work at 7.30 and finished at 4pm. It was a long day but things wound down in the last hour. Someone would go round taking orders for ice creams. Someone (often me) would give a guided tour to groups of tourists. If it had been dry, we watered the site thoroughly and covered it in plastic sheeting. This made it easier to see the layers and helped preserve the wood.

At four, we stopped work and went off for a shower in the nearby fire station. Boys and girls together, although shy girls had their own slot later. Shy boys had to grin and bare it.

There was a fest (party) in the house most Thursdays. This meant a visit to the Vinmonopolet to buy a bottle of the aptly-named vanlig rødvin (ordinary red wine) to supplement the Dahl's beer we ordered through the site office. The state-owned Vinmonopolet, which resembled a chemists' shop, was the sole (legal) source of wines and spirits for a city of 135,000 people.

The fests were often themed events and fancy dress was prefered. One of the most memorable creations was by Gerry Pratt, who came as a cactus to the Wild West Fest.

There was singing, dancing (One Step Forward), Norwegian leg wrestling, and pea soup eating competitions. These were almost always won by Howard Murray, who moved the spoon to his mouth in a steady unrelenting pace while maintaining eye contact with his opponents, who had started fast but were now sweating profusely as they struggled with the sixth bowl.

We also went out bopping at Strosse and blagged our way into student union dances. Dave the Rave drank Lumumbas with his poker-playing pals. Trondheim parties often featured karsk - sweet black coffee laced with hjemmebrent - 96% moonshine spirit. This drink enhanced the magic of the timeless midsummer nights as it left the body's motor functions unimpaired long after the mental faculties had closed down.

There were fishing trips, games of rounders up by Kristiansten fortress and weekends on the other side of the fjord, falling asleep in mossy hollows in the rocks as the last plumes of campfire smoke spiralled up into the first rays of dawn.

January 1985

The huge ferry pulled out of Oslo harbour bound for Copenhagen. I waved goodbye to Kathy Elliott, a tiny solitary figure on the dockside below me. Ten years earlier, I had arrived in Norway, roving out on a bright May morning, and now I was leaving it (and archaeology) on a freezing dark winter's evening. My heart had been broken for the third time (twice by the same person) and I had discovered that writing reports was much less fun than digging. I had become disillusioned with medieval archaeology - "a very expensive way of telling us what we already know"

Sitting on the train about to leave for Esbjerg, I was almost sick with sadness. Looking back I can see that these were rebirth pains - it was time to wrench myself away from a person, a place and a job that I loved. The compartment door slid open and two young women came in - a blonde Swede and a dark Venezuelan - both heading for the same ferry as me. They were to be the unwitting midwives of my rebirth.

The author with Mari Marstein

The author with Mari Marstein

Quite a few Trondheim diggers died too young - Gordon Parry, Barry Warren, Shaun Gegg, Martin Howe, Gerry Pratt, Clifford Long and Sæbjørg Nordeide -

Links:

Trondheim library site reports - mostly in Norwegian

Trondheim Diggers Facebook Group - FB group for library site alumni

Arkeologi i Trondheim - frequent FB posts on finds from Trondheim sites

Comments powered by CComment