‘I keep saying another metre and that will be it, but I said that 2m ago’: The excavation of the massive Roman wells and their bucket chains at 20-30 Gresham Street

Ian Blair

In 2001 a film crew followed the nine-month long excavation at 20-30 Gresham Street (GHT00), also known as Blossoms Inn, for a Time Team Special ‘Londinium, The Edge of Empire’ which aired a year later in April 2002:

The large footprint of the development entailed the demolition of thirteen adjoining buildings including the State Bank of India on the west side of the site, completed only twenty-three years earlier and the site of the DUA Milk Street (MLK76) excavation.

The site lay due south of the Roman amphitheatre and was expected to produce a classic sequence of well-preserved masonry and clay and timber buildings, aligned upon, and extending back from a known east-west Roman road. It soon became apparent though, that this supposition was not entirely correct, as although the road and its flanking ditches duly appeared, the expected sequence of buildings aligned upon it were largely absent.

In their place on the north side of the road emerged a large, waterlogged pond-like feature derived from brickearth and gravel quarrying in the early Roman period, the most notable find from its lower fill being the left hand and forearm from a slightly over life-size bronze or copper-alloy arm. The arm was presumably part of a public statue, perhaps of the Emperor Nero deliberately broken up after his suicide in AD68. Archaeologist Ben Savine found it with his mattock, with the resultant dink in its surface still bearing testament to this, but then who would expect to find a severed arm in the bottom of a pond? ‘Oh my God! a limb from a dismembered body’: the severed arm in the pond

‘Oh my God! a limb from a dismembered body’: the severed arm in the pond

On the opposite south side of the road three smaller, but none-the-less sizeable, waterlogged features had begun to emerge whose original purpose was uncertain. As more of their wet claggy backfill was removed their function became clearer, as each contained a substantial, partially robbed, timber lining, and the only conclusion was that these were massive well shafts: albeit six-times the size of the average Roman box-lined well, which have been found on countless archaeological sites across the City of London and Southwark. Excavation in progress of the early west well at 20-30 Gresham Street: with (from top to bottom): Satsuki Harris (on metal detector), Rosie Joynson, Katherine Quinteros (Q), and Ian Blair At the same time as filming at 20-30 Gresham Street, Time Team were also shooting another special on the much larger ‘Big Dig’ excavation in the heart of Canterbury. Because Tony Robinson and the other Time Team co-presenters were engaged on the Kent project, none were ever to visit the London site and we were left blissfully alone. The advantages of this arrangement were, that we would simply notify the film crew as and when we had found something notable, or at pivotal moments in the excavation, so there was a sense of the project being filmed in real time archaeologically speaking, and I think a more coherent and ordered picture of a pressured urban excavation afforded.

Excavation in progress of the early west well at 20-30 Gresham Street: with (from top to bottom): Satsuki Harris (on metal detector), Rosie Joynson, Katherine Quinteros (Q), and Ian Blair At the same time as filming at 20-30 Gresham Street, Time Team were also shooting another special on the much larger ‘Big Dig’ excavation in the heart of Canterbury. Because Tony Robinson and the other Time Team co-presenters were engaged on the Kent project, none were ever to visit the London site and we were left blissfully alone. The advantages of this arrangement were, that we would simply notify the film crew as and when we had found something notable, or at pivotal moments in the excavation, so there was a sense of the project being filmed in real time archaeologically speaking, and I think a more coherent and ordered picture of a pressured urban excavation afforded.

Following the discovery of the massive Roman wells, little prompting, or encouragement, was needed however, as progressively the film crew made ever more frequent visits. As the excavation of the west well continued ever downward, I made the first of what were ultimately to be several similar asides to camera: ‘I would be surprised if it was going to much deeper than another metre or so. Famous last words!’ . Not long before reaching the base of the well shaft at a depth five metres below the original Roman ground surface, and by now painfully aware of what I had speculated on to camera previously, I could only but smile and say: ‘I keep saying another metre and that will be it. But I said that 2m ago!’.

Dendrochronological dating of the internal cruciform cross-bracing timbers provided a consistent date of AD63, putting the construction of this the earliest well on site, to the period of rebuilding and the expansion of infrastructure, after the Boudican revolt of AD60/61. Internal cruciform cross-bracing structure in the west well at 20-30 Gresham Street: at least the surplus water came in handy for swabbing the timbers down! Treading water in the lower levels of the well are Katherine Quinteros (Q) and Ian Blair

Internal cruciform cross-bracing structure in the west well at 20-30 Gresham Street: at least the surplus water came in handy for swabbing the timbers down! Treading water in the lower levels of the well are Katherine Quinteros (Q) and Ian Blair

When the base of the well was finally reached, a well-preserved halved barrel, made from alpine softwood, probably larch or silver fir, and bound with hazel hoops, was found. The barrel was cut into the impermeable London Clay and contained parts of three hollowed-out oak water-boxes from a mechanical water-lifting device or bucket chain, several iron rivets or connecting pins, and a small wooden roller. The question which had perplexed me, and occupied my thoughts throughout its excavation, of why you would build a well structure of this enormous size, and how you could efficiently draw water from its depths, was now conclusively solved. The bottom of the west well finally reached Time Team director and cameraman Graham Johnston and Ian Blair discussing the halved barrel and its contents

The bottom of the west well finally reached Time Team director and cameraman Graham Johnston and Ian Blair discussing the halved barrel and its contents

Softwood halved barrel at the bottom of the west well, one of the hollowed-out oak water-boxes can be seen in situ in the left-hand side of the barrel

Softwood halved barrel at the bottom of the west well, one of the hollowed-out oak water-boxes can be seen in situ in the left-hand side of the barrel

In the following weeks, the base of the adjoining east well, constructed around AD108, was also reached at a similar depth, where it too bottomed out on the surface of the London Clay. Astonishingly, the remains of a second much heavier-duty bucket chain, composed of wrought iron linkage and open-topped box-buckets, were found at its base. Chris Clarke & Catherine Edwards (Cat) in the base of the east well recording the remains of the heavier-duty wrought iron bucket chain and its burnt box-buckets

Chris Clarke & Catherine Edwards (Cat) in the base of the east well recording the remains of the heavier-duty wrought iron bucket chain and its burnt box-buckets

It was this bucket chain that was later the focus of a full-scale working replica of a Roman water-lifting machine, that opened to the public in the Rotunda Garden outside the Museum of London in November 2002. ‘Hadrian’s Well’ was a subsequent Time Team Special, that followed the course of this unique reconstruction project ‘Working Water: Roman technology in action’ sponsored by Swiss Re. The Theoretical analysis and design of the water-lifting machine was developed by engineers Dr Robert Spain and Tony Taylor. The prototype and finished machine were built by Peter McCurdy and his team at McCurdy & Co.

Early in the design stage of the project, it was decided that the reconstruction would be powered by a geared capstan drive and not a treadwheel, not only for the obvious health and safety considerations, but importantly to allow members of the public, including children, to participate in powering the water-lifting machine.

The full-size reconstruction of the Roman water-lifting machine (based on the bucket chain from the east well at Gresham Street), being demonstrated in the Rotunda Garden outside the Museum of London in 2006. Press-ganged into service are Meriel Jeater and Patrizia Pierazzo with two smaller assistants.

The full-size reconstruction of the Roman water-lifting machine (based on the bucket chain from the east well at Gresham Street), being demonstrated in the Rotunda Garden outside the Museum of London in 2006. Press-ganged into service are Meriel Jeater and Patrizia Pierazzo with two smaller assistants.

Initially demonstrated daily for nine months, and then periodically, it was finally systematically dismantled in 2010, when a new home was found for it, the Museum of London having donated it to the Ancient Technology Centre (ATC), in Wimborne, Dorset. It was reassembled on the site and a grand opening took place in May 2011, where it is still well maintained and demonstrated to this day. The long term aims of the ATC is to test the machine with regular use and monitor wear of components and the actual quantities of water moved by the device. This in turn will provide information and insight as to the efficiency of water movement in Roman London.

Postscript

The saying: ‘You wait ages for a bus, and then three come at once!’, could equally apply to the Roman bucket chains discovered in 2001, as soon after the completion of the excavation of the Gresham Street wells, Dan Swift and his team on another MoLAS site at 12 Arthur Street (AUT00), adjoining the west side of London bridge, uncovered a large rectangular Roman well. In its fills, they too found the well-preserved water-boxes from a bucket chain, identical to those found in the west well, but importantly with one example with the wrought-iron linkage still articulated.

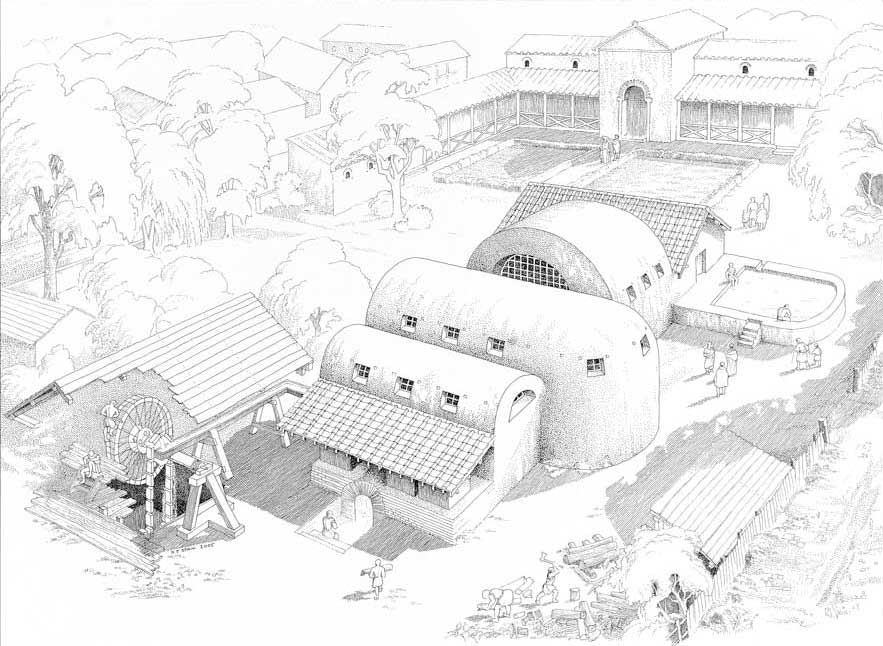

However, none of these were the first remains of a bucket chain to be found on an excavation in the City of London, as forty-six years earlier in 1955 Ivor Noël Hume had unknowingly found the remains of two identical (though more fragmentary) water boxes, in a large well or water-tank on the north side of the Cheapside Roman baths.  Artist’s impression showing the Cheapside Roman baths complex and well-house looking south-east. Drawing by Robert Spain reworked from an Alan Sorrell original

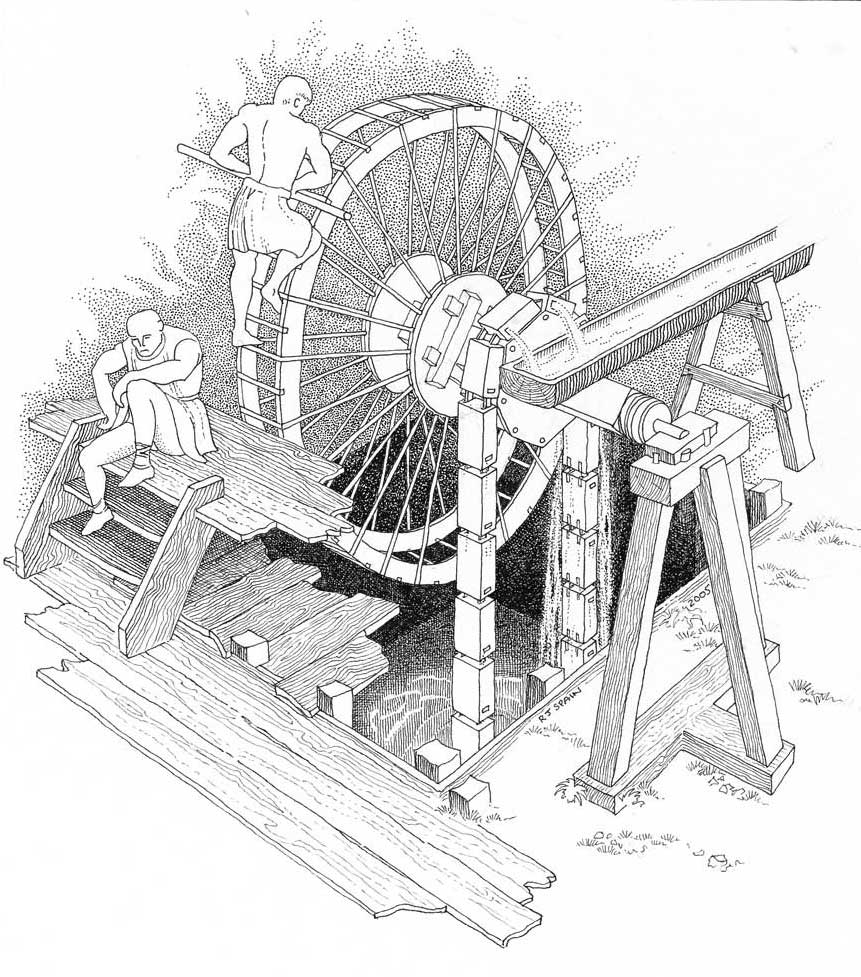

Artist’s impression showing the Cheapside Roman baths complex and well-house looking south-east. Drawing by Robert Spain reworked from an Alan Sorrell original Detailed drawing by Robert Spain of externally driven treadwheel in operation at the Cheapside Roman baths. The hollowed-out oak water-boxes (with side entry/exit port) are identical to the bucket chains found at Gresham Street and Arthur Street

Detailed drawing by Robert Spain of externally driven treadwheel in operation at the Cheapside Roman baths. The hollowed-out oak water-boxes (with side entry/exit port) are identical to the bucket chains found at Gresham Street and Arthur Street

Less well preserved then the later examples their function was unclear, and Noel speculated that given that they had a similar dimension to box-flue tiles, that they could represent part of a hypocaust system, even showing one of the boxes in a small sketch in his notebook at roof level acting as a louvre, with wisps of smoke curling from its side.

It was pleasing that when the ‘Hadrian’s Well’ Time Team Special was filmed in 2002, that Noel was able to come from his home in Williamsburg, Virginia to the Museum of London Archaeological Archive at Eagle Wharf Road in Hackney and do a piece to camera. Being reunited not only with his ‘newly identified’ water-boxes from the Cheapside Roman baths, but to also see the better-preserved but identical examples from the excavations at Gresham Street and Arthur Street.

Unsurprisingly, in the intervening twenty years no other examples of massive Roman wells, of a size large enough to house a mechanical water lifting device, or the remains of components of a bucket chain, have been found in London. So, the long wait at the archaeological bus stop for the next one to come along goes on, but it is conceivable that the last bus left in 2001.

Photos © MOLA

Comments powered by CComment