Telling Tales: a Baker’s Boy in Pudding Lane

Gustav Milne

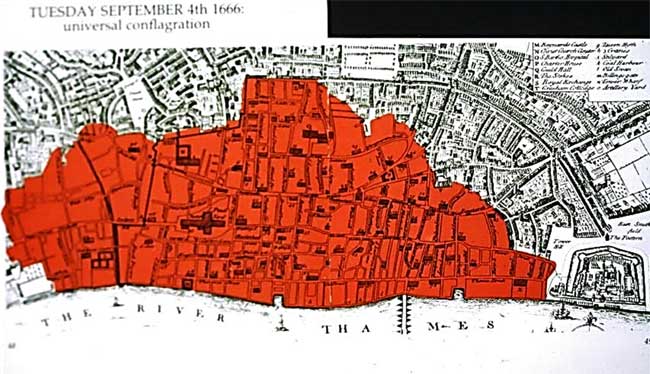

One of the few dates in English history that every school person knows is “1666: the Great Fire of London”.

Over some five days and nights, that conflagration destroyed over 13,000 houses, St Paul’s, 87 parish churches, Guildhall, Custom House and many thousands of pounds-worth of goods stored in shops and warehouses (“of which the City was at that time very full”)

Great Fire of London, as depicted in a contemporary drawing by unknown artist

Great Fire of London, as depicted in a contemporary drawing by unknown artist

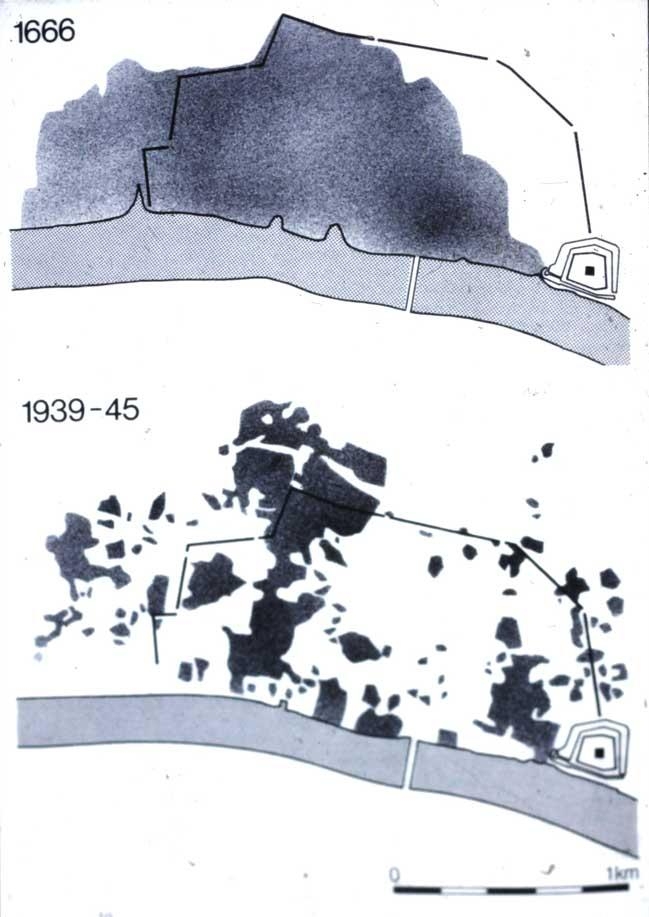

That catastrophe still merits the superlative description The Great..: the area actually within walled enceinte of the historic City destroyed in the 17th-century fire was actually more extensive than that flattened during the Blitz in 1940-45

Destruction in City caused by Blitz 1940-45, and by Great Fire of 1666 (C. Harrison)

Destruction in City caused by Blitz 1940-45, and by Great Fire of 1666 (C. Harrison)

The Great Fire has thus been the subject of many books and TV programmes, while the physical evidence of the thick layers of debris associated with it have been recorded on many archaeological investigations in the City. But can archaeology add to our understanding of this well-documented tragedy?

AN EXCAVATION IN PUDDING LANE

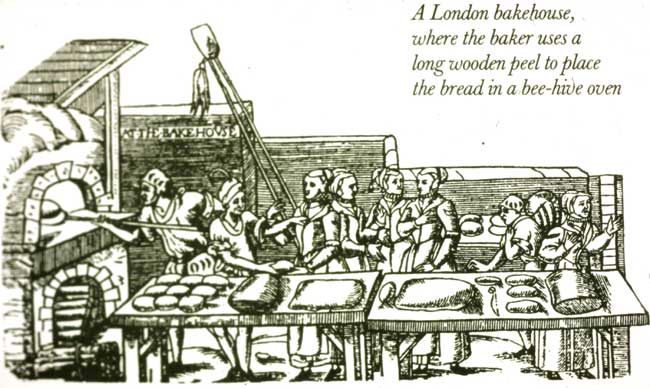

Of all the archaeological sites that have investigated the Great Fire, the excavations on the eastern side of Pudding Lane in 1979 are perhaps the most famous. The site of what is now Peninsular House lies at the junction of Monument Street and Pudding Lane: the north-west corner of that modern building impinges on the site of the bakery where the Great Fire actually began. A 17th-century bakery with bundles of faggots for fuel on floor next to oven (Historical Publications)

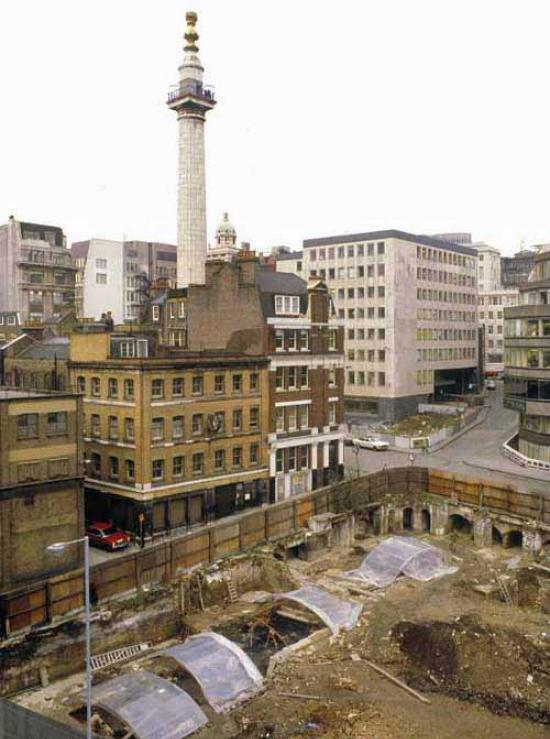

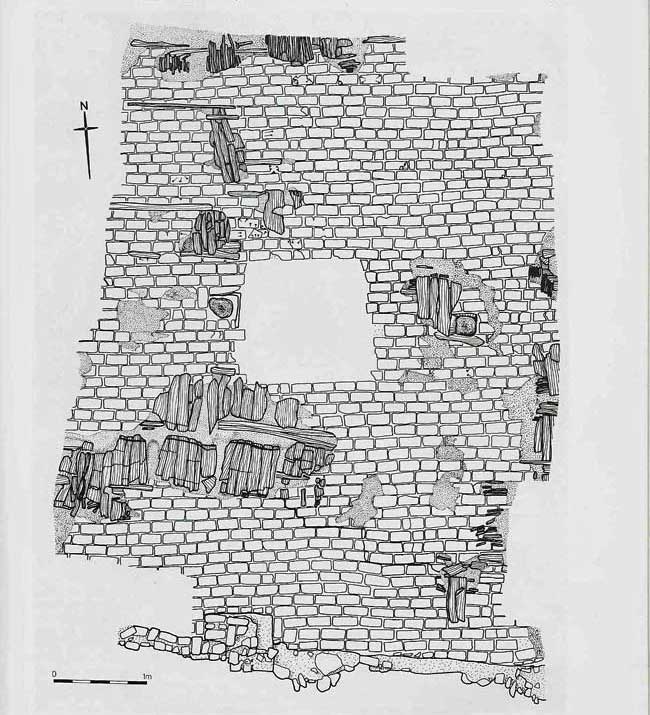

A 17th-century bakery with bundles of faggots for fuel on floor next to oven (Historical Publications) Archaeological excavations on eastern side Pudding Lane, looking NW. Thomas Farriner's bakehouse would have lain partially under northernmost shelter: the cellar next door exposed in the centre was fully excavated in 1979 (PEN79) (c Museum of London)We conducted a brief four-month excavation there over the bleak winter of 1979-1980, with a small team of professionals during the week, and with an expanded team of our colleagues from the City of London Archaeology Society at weekends. We opened a discontinuous 5m-wide north-south trenches hard up against the eastern Pudding Lane frontage. At its northern end, all trace of the 17th-century bakery had been removed by later negative terracing of the hillside which sloped down to the Thames. However, just to the south, the well-preserved evidence of a brick-lined cellar of a neighbouring building was uncovered, and we began excavating the thick dumped deposits of late 17th-century date that had infilled it.

Archaeological excavations on eastern side Pudding Lane, looking NW. Thomas Farriner's bakehouse would have lain partially under northernmost shelter: the cellar next door exposed in the centre was fully excavated in 1979 (PEN79) (c Museum of London)We conducted a brief four-month excavation there over the bleak winter of 1979-1980, with a small team of professionals during the week, and with an expanded team of our colleagues from the City of London Archaeology Society at weekends. We opened a discontinuous 5m-wide north-south trenches hard up against the eastern Pudding Lane frontage. At its northern end, all trace of the 17th-century bakery had been removed by later negative terracing of the hillside which sloped down to the Thames. However, just to the south, the well-preserved evidence of a brick-lined cellar of a neighbouring building was uncovered, and we began excavating the thick dumped deposits of late 17th-century date that had infilled it.

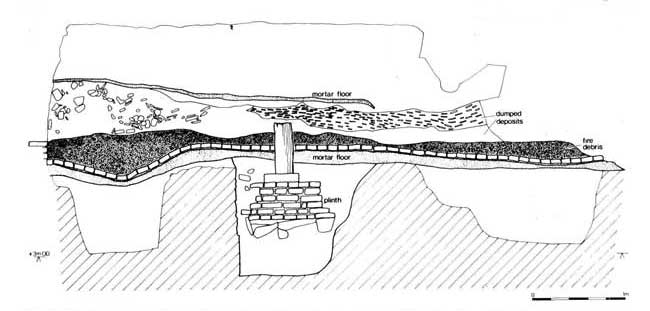

Section drawing showing debris deposits overlying carbonised laver sealing cellar floor (C. Harrison)

Section drawing showing debris deposits overlying carbonised laver sealing cellar floor (C. Harrison)

BUILDING DEBRIS

The roof of the former 17th-century building was represented by fragments of pegged roof tile characteristic of local manufacture from the late 15th century, many badly burnt, contorted and warped by the fire, with some fragments having exploded with the intensity of the heat. Then there were bricks, mortar and other material showing signs of burning and vitrification, clearly representing the debris from a collapsed fire damaged structure (s). The presence of over 100 whole hand-made stock-moulded bricks in these dumps suggests that the debris had not been sorted. Molten and twisted nails were mixed in with the building debris together with fragments of window glass, iron brackets of varying sizes, part of a pivot, a hinge and a lock and four fragments of badly burned and partially vitrified stove tiles were also recovered. This assemblage presumably could be associated with the occupation of the upper floors.

Many broken earthenware storage jars of the same hitherto unknown type were also found, together with a large collection of metal hooks and eyes contorted by the heat. This suggests that the ground floor over the cellar was occupied by a shop. There were also two unused tin glazed polychrome tiles, which had fallen so that their lower edges were just over the scorched cellar floor. Only the lower edge of the tiles was burnt, demonstrating that at least some of the debris had been introduced into the cellar while the fire was still smouldering, so cannot have been brought from a great distance.

FUEL FOR THE FIRE

All this debris lay over a thick black carbonised layer that sealed the scorched brick cellar floor.

Thick carbonised layers covered much of the scorched brick floor (c Museum of London)

Thick carbonised layers covered much of the scorched brick floor (c Museum of London)

Following the detailed dissection of the debris dumps, as the supervisor of a site I was now eager to persuade the excavators to speed up their work. After all, this was rescue archaeology: we had a pressing deadline and were ever mindful of the other areas of the large site requiring attention in the limited available daylight hours we had. However, Dave Bowler, one of highly skilled archaeologists faced with the excavation of the back carbonised layers just being exposed, was not going to be rushed. With hindsight he was of course soon proved right, and spectacularly so.

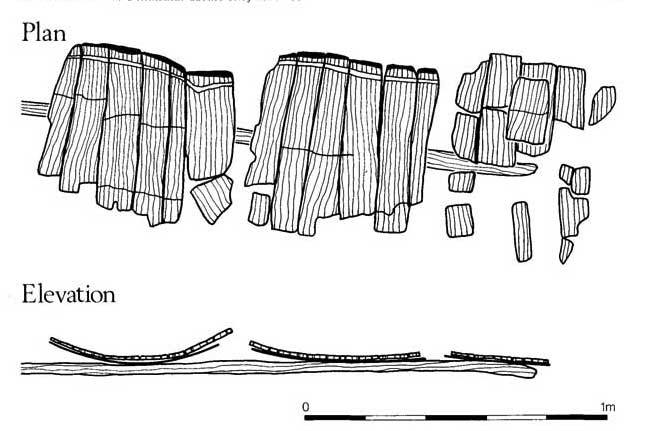

Working in the depths of winter with great patience and skill, the small team methodically, indeed magically, revealed the well preserved, but completely carbonised contents of the cellar. The complex investigation and planning took some two weeks, and involved a relatively novel technological innovation: the use of an industrial “Henry” vacuum cleaner. This machine had only recently been introduced to City archaeologists by John B. Easton. In those days, not every site was blessed with a formal electrical supply, but a power source was needed and therefore somehow found. This machine was a game changer, when set alongside the skilful use of a delicate plaster’s leaf (another JBE promotion) to surgically dissect the burnt deposits. As Chrissie recalls, each evening the team went home completely blackened “like coal-miners or chimney sweeps”, much to horror of City office workers. Undaunted, they eventually exposed, cleaned, photographed and planned their discovery: five timber racks upon which the carbonised remains of twenty barrels made from oak staves closely-bound with ash hoops. To say this was a truly remarkable example of the excavators art would not be an understatement.

Photo Careful excavation of the carbonised layer revealed a line of burnt barrel staves (c Museum of London)

Photo Careful excavation of the carbonised layer revealed a line of burnt barrel staves (c Museum of London)

Plan showing remains of the carbonised barrels lying on racks on cellar floor (C. Harrison)

Plan showing remains of the carbonised barrels lying on racks on cellar floor (C. Harrison)

The barrel staves were lifted, revealing the ash hoops that bound the barrels, as well as long racks upon which the barrels had been stored. (c Museum of London)

The barrel staves were lifted, revealing the ash hoops that bound the barrels, as well as long racks upon which the barrels had been stored. (c Museum of London)

Plan showing detail of the ash barrel hoops (C. Harrison)

Plan showing detail of the ash barrel hoops (C. Harrison)

Subsequent analysis showed the these features represented a warehouse storing wood pitch, probably derived from Stockholm Tar, a material widely used, for example, for waterproofing the hulls of ships. Unfortunately it is also very combustible: the burning bakehouse was right next to a bomb waiting to explode. So, although the patience of David Bowler, Kirsten Svenson-Taylor and Chrissie Harrison did not discover the cause of the Great Fire of London, they did find the fuel for it, the reason why what was initially seen as just another minor London fire became a major catastrophe.

POINTING THE FINGER

So what or who started the Great Fire? Research by Professor Kate Loveman (University of Leicester) identified one Thomas Dagger, an apprentice in the infamous bakehouse, as the person who first raised the alarm for the Great Fire of London. But that’s not all: further research by the DUA suggests that he also actually started the Fire. According to the incomparable Walter G Bell's Great Fire of London (1920) and other printed sources, it seems that Thomas Dagger, the baker’s boy, initially admitted as much before the fire got completely out of control. However, as the dreadful scale of the disaster dramatically unfolded, and vengeance was vociferously sought, his story rapidly changed and a new scapegoat was conveniently found.

The fire even destroying St Paul's, the largest building in the City (W.Hollar)

The fire even destroying St Paul's, the largest building in the City (W.Hollar)

The smoking gun is in a report written in London in September 1666 by people who were actually there at that time. It was initially published in Italian, and printed in the Calendar of State Papers Domestic vol 175, no 164 , but subsequently re-printed in Bell’s monumental work (1920, p321). The translation states that:

"..the baker's boy (ie Thomas Dagger) having placed some twigs (firewood) in the oven to dry, about midnight on Saturday they caught fire, setting the whole house ablaze..."

So Dagger arguably but unwittingly started the blaze. Although he subsequently alerted the household to the danger, from which the baker Thomas Farriner Snr, his son Thomas Farriner Jnr as well as daughter Hannah all managed to escape, for reasons that are unclear, the poor maid was left by them in an upstairs room to perish in the flames.

Dagger’s blurted confession seems to have been made very soon after the fire had broken out (but was not yet an unstoppable conflagration) since it is included in the letter alongside contemporary comments reportedly made by Sir Thomas Bludworth, the Lord Mayor at 3am on Sunday 2nd September. He had just been advised by ward officials to pull down neighbouring houses and a shop to create a firebreak, and thus contain the blaze. The letter quotes him as complaining that “when the houses have been brought down, who shall pay the charge for rebuilding them?” to account for his slowness to address the unfolding crisis. The remains of the shop that could or should have been pulled down to prevent the fire spreading was probably that excavated by archaeologists from the Museum of London in 1979, with its barrels of pitch waiting to explode.

Over the next week, as the stark horror of the events became ever clearer, questions were asked and retribution demanded. This was an unstable political period when England was at war with the Dutch and the catholic French were viewed with increased suspicion in protestant London. As early as the 3rd of September, as the fire continued to rage unabated, a Dutch baker in Westminster was almost beaten to death in the street and rumours of Papist fireballs being thrown into houses abounded.

Plan showing extent of fire on Tuesday, with most of the ancient City ablaze (C. Harrison)

Plan showing extent of fire on Tuesday, with most of the ancient City ablaze (C. Harrison)

BLAME GAME

It was obviously time for Dagger and the Farriners to change the narrative to absolve themselves from all blame. Indeed, by October 1666, Thomas Farriner Snr gave a very different story in the Old Bailey Sessions at the trial of Robert Hubert, a rather deluded Frenchman who falsely admitted to starting the conflagration. Thos Farriner claimed he had, after midnight on Saturday 1st September, 'gone through every room (in the bakery) and found no fire, but in one chimney...which fire he diligently raked up in embers..." . However -conveniently ignoring Dagger’s admission- Farriner then stated that the house "was absolutely set on fire on purpose" ie by a fire bomb thrown into the house by Robert Hubert. The trial reluctantly condemned Hubert to death: he was hanged in public on October 29th, his body torn down by a baying mob and ripped limb from limb (Hollis 2008, 141). His death warrant had been signed off by Robert Penny, John Lewman and Francis Gunn, as well as the Pudding Lane family group of Thomas Farriner (Snr), Thomas Farriner (Jnr), Hanna Farriner as well as Thomas Dagger himself. An innocent man died to save their skins, if not their souls (Bell 1920, p353-4).

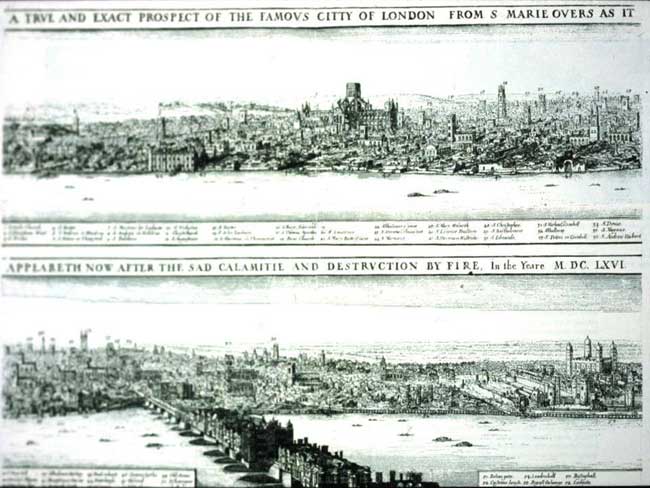

By the end of the week, the fire had been contained, but the City was a blackened ruin as shown in this contemporary panorama (W. Hollar)

By the end of the week, the fire had been contained, but the City was a blackened ruin as shown in this contemporary panorama (W. Hollar)

Three months later, in January 1667 a detailed parliamentary enquiry finally reported on the cause. It uncovered no sensible evidence for Papist plots, malevolent Dutch designs, or Hubert’s fire bombs. Instead it declared that it was none other than “by the Hand of God upon us, a great wind and the season being so very dry”. The apprentice’s admission that he had placed bundles of firewood “in the oven to dry, about midnight on Saturday they caught fire, setting the whole house ablaze” was never mentioned and firmly forgotten. However, following a magnificent major rebuilding programme, the City subsequently rose from the ashes, while Dagger and the Farriners lived to bake another day.

DUA excavation team (PEN79), including Kirsten Svenson-Taylor (front row, left), David Bowler (front row, centre) and Chrissie Harrison (back row, right) Photo N Bateman

DUA excavation team (PEN79), including Kirsten Svenson-Taylor (front row, left), David Bowler (front row, centre) and Chrissie Harrison (back row, right) Photo N Bateman

© Gustav Milne 17/04/2024

FURTHER READING

Bell, WG, 1920 The Great Fire of London, London

Hollis, L, 2008 The Phoenix, London

Milne, G, 1986 The Great Fire of London, London

Milne, G & Milne C, 1985 ”A Building in Pudding Lane destroyed in The Great Fire of London”,

Trans LAMAS 36, 169-182

Comments powered by CComment