Telling Tales: a Thames Tug of War

Gustav Milne

“Did I ever tell you my Dad worked on a Thames tug in the war?” No she hadn’t. What follows is as much of his story as can be pieced together, 80 years later.

Another Great Fire of London Mary Evans Picture Library

Another Great Fire of London Mary Evans Picture Library

One of the challenges faced by those born after the Second World War trying to understand those dark days, is the profound difference between statistics, regimental histories and political narratives (Churchill’s History of the Second World War runs to six volumes) and the lived experiences and varied perspectives of the mortal men and women who simply did their bit. This was brought home to me after discussion of the Thames at War book with my sister-in-law, the irrepressible Sue Crossing. She said “Did I ever tell you my Dad worked on a Thames tug in the war?” No she hadn’t. What follows is as much of his story as can be pieced together, 80 years later.

Alfred Crossing was born in East London in December 1919 and left school aged 14. His first job was as the deck boy on SUN V, one of the 350 or so hard-working steam tugs then working on the busy River Thames. The vessel had been launched in 1915 at Earles Shipyard in Hull, and purchased by WHF Alexander’s company in London. It was 105ft in length, with a beam of 25’6ins and became Alfred’s home from home. This was when the Port of London was the largest in the world, when cargoes arrived here from all corners of globe. Those large ships often had to be manoeuvred by those tiny tugs under tow, in and out of narrow dock gates or up against riverside quays.

SUN V, a hard-working steam-powered Thames tugboat

SUN V, a hard-working steam-powered Thames tugboat

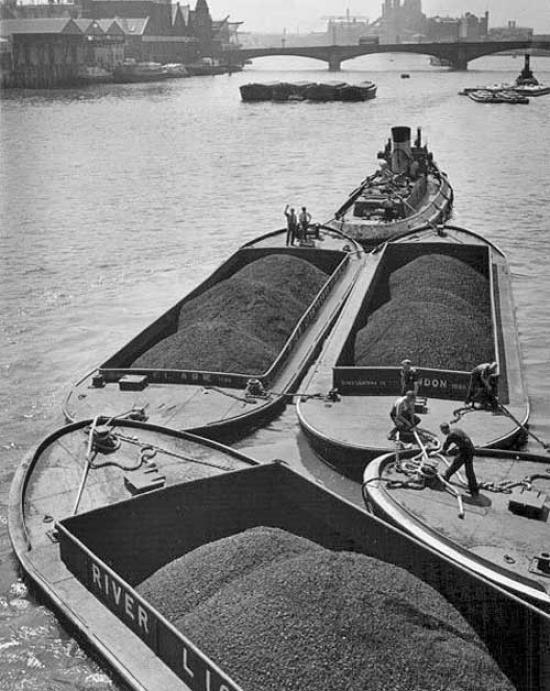

When cargoes were offloaded from those large ships onto lighters (engine-less barges) the tugs then towed them tethered together, one,two or six at a time- to the many wharves and warehouses lining the banks of the river.It was demanding work for the port’s essential workhorses, in all weathers and all seasons (even ropes can freeze).

Tug crews usually worked a six-day week, but often in sixteen-hour shifts from 6am to 10pm, one day on, one day off. However, because of vagaries of the tide, the times of shifts could vary, sometimes running a full 24 hours from 6am one day to 6am the next. There was no radar and no Thames Navigation Service to guide the vessel: the skipper relied on hard-won knowledge. And there was no onboard telephone: the tugs would regularly come alongside pier heads or other vantage points where the skipper or mate could land, find a public telephone and ring head office to relay progress and receive fresh orders.

One tiny tug navigates a huge consignment of coal through bridges and avoiding other Thames traffic to feed one of London's riverside power stations

One tiny tug navigates a huge consignment of coal through bridges and avoiding other Thames traffic to feed one of London's riverside power stations

The tug’s crew would be a complement of about five with self-explanatory job titles: the skipper, his mate, and engineer, a greaser and then, finally, the deck boy. He had many duties: the first one was lighting the paraffin lamps, which (in winter) included the navigation lamps which had to be working before the tug could get underway. Then the galley fire had to be lit to get the kettle boiling for the essential mugs of tea. Next job was on deck, playing out the thick ropes for the lightermen to attach to the barges. There was much to do and much to learn, and after a seven-year hands-on apprenticeship, he could apply for a Waterman and Lighterman’s licence. But just before that, the war intervened.

On December 12th 1939, SUN V was requisitioned by the Royal Navy for the duration, its crew “joining” the ranks of the Royal Naval Voluntary Reserve. Like the rest of the country, the port of London was placed on a war footing, since it played such a crucial role as a national distribution and supply centre. The tugs and barges in the docks were an essential component of that complex system.

In addition, they undertook patrol work in the Thames estuary, looking out for mines or for enemy aircraft hoping to attack convoys of merchant shipping carrying desperately need supplies, or assisting vessels in need. For example, in August 1940, SUN V and SUN VIII had to refloat the City of Dundee after she had run aground on the treacherous Thames sandbanks. This could only be attempted when the tide was right at 23.35 (i.e. in the middle of the night). Four days later, SUN VIII tried to refloat another stranded ship, the SS Brisbane ablaze from stem to stern, but she could not be saved. Neither could tug SUN VII: she struck a mine in the estuary on 6th March 1941 and sank with the loss of her crew of five.

During the war, civilian vessels like this tug requisitioned by the Navy were often armed: this is a Lewis gun mounted on the open deck. However, if you could see an enemy aircraft coming towards you, then he could probably see you…. Photo by Harold Russel

During the war, civilian vessels like this tug requisitioned by the Navy were often armed: this is a Lewis gun mounted on the open deck. However, if you could see an enemy aircraft coming towards you, then he could probably see you…. Photo by Harold Russel

The requisitioned tug SUN VII, flying the naval ensign and painted grey, on the Downs Patrol before she struck a mine and sank with the loss of all hands.

The requisitioned tug SUN VII, flying the naval ensign and painted grey, on the Downs Patrol before she struck a mine and sank with the loss of all hands.

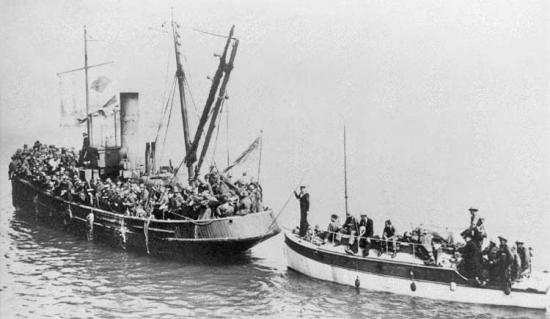

SUN V and nine of the other SUN tugs also served in the Dunkirk evacuation. In May 1940 the German Army Blitz-Kreiged their way through France. They overwhelmed the French army and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), surrounding them on the exposed coast near Dunkirk. An evacuation plan was hurriedly prepared, in which a vast armada of over 700 small vessels collected from ports and rivers in southern England would collect as many soldiers as possible from the open beaches and transfer them to the 220 larger Royal Naval ships moored in deeper water. That was the general idea, give or take mines, the close attention of the Luftwaffe bombing and strafing them, and the impending advance of the German army’s Panzer divisions. The “Little Ships” flotilla included many fishing boats, sixteen Thames Sailing Barges, twenty RNLI lifeboats, ten SUN tugs, pleasure steamers such as the Medway Queen and the Marchioness, as well as the fireboat Massey Shaw.

All the SUN tugs fortunately survived the ordeal. The very varied roles played by them in the evacuation can be readily reconstructed from such official records as are available and from the recollections of the crews, many of whom would have been Alfred’s friends and colleagues. To take a few examples, starting with tug SUN VIII: at 21.00 hours on 30th May, she started towing 14 lifeboats (to save their fuel) at night from Tilbury out to Southend, arriving at 23.00. At 4.30am the very next morning she left for Ramsgate, arriving there at 11.20. By 14.30 she was underway to Dunkirk where she anchored at 22.00. The next day, by 2am in the morning, she started embarking as many soldiers as she could in the dark, and left for Ramsgate at 4am, disembarking her human cargo there at 9.15am. These were long day (do the maths). As one crew member from a Thames tug reported, “I had been on my feet from 0700 29thMay in a small craft, the only food eaten (for the next two days) was one tin of herrings, one tin bully beef, two slices of bread and four cups of tea, no sugar. We simply had not time to eat” (Atkin 2020, 2010).

And then there was tug SUN XII, the crew of which included Alfred Barnes, aged just 14 ½ (who hadn’t told his mum he was going) the youngest participant in the whole operation. On 29th May the tug left Tilbury towing four capacious Thames Sailing Barges Thyra, Royal, HAC and Beatrice Maud, all packed with supplies, arriving at 15.00 in Ramsgate, the central control port for Operation Dynamo. She then left there for France an hour later, this time towing two more Sailing Barges, Ethel Everard and Tollesbury with supplies of food and water for the troops. In spite of attacks from the Luftwaffe, she arrived at Dunkirk at night some seven hours later, and set the flat bottomed barges on the beach. The cargoes having been discharged, she embarked a consignment of soldiers, leaving for Dover 4am. In spite of an attack by enemy aircraft, she arrived there some seven hours later. The harbour at Dover, as can be imagined, was overcrowded with ships looking for berths to discharge the weary and the wounded, while other ships, large and small, were trying to leave. At 20.30 that night, there was a terrible accident, when the destroyer HMS Worcester collided with the cross- channel ferry Maid of Orleans over-filled with evacuated troops, many of whom were thrown into the water. SUN XII was immediately sent to save as many as she could, but not all were rescued: a terrible irony to be rescued from Dunkirk only to drown in Dover harbour.

SUN III had towed four barges from Southend to Dunkirk. Wally Jones, the tug’s engineer, actually pulled his own brother from the beaches of Dunkirk (what were the chances?) and brought him safely home with 111 other soldiers. She later came across a lifeboat in trouble, and, once the RAF had seen off the menacing German Doniers, was able to take on board the 148 soldiers and get them back home.

Master WA Fothergill took Tug SUN X out of Dover on June 2nd at 3.15pm, arriving at Dunkirk at 10.15pm. They saw the town in flames, with shells and bombs exploding, and a pall of black smoke blowing westwards. They were then asked to assist moving troops from a transport that had grounded inside the harbour. She picked up several boats loaded with men and took them outside the harbour. She then took up her originally allotted position to collect more boat-loads of troops while enemy aircraft overhead kept both her gunners busy. Having embarked 300 soldiers, she was ordered to proceed alongside the main mole, to shunt the transports closer to the mole, as required, staying close to the mole until dawn. She was then ordered back to Dover, picking up two boats in difficulty enroute and towing them home arriving at Admiralty Pier at 9am on June 3rd. As for SUN XV, even though she herself had been damaged when she struck wreckage underwater, still managed a successful journey back with her evacuated soldiers.

Similar stories are associated with SUN XI , whose crew included a 15-year old boy Leo Desmond. He recalls counting some 85 German aircraft overhead during the voyage from Ramsgate as they were towing up to 14 barges packed with supplies for Dunkirk. Bombs and bullets were flying as they landed. Once the cargoes were discharged, over 100 soldiers were crammed onto the tug. She then found a broken down barge full of wounded soldiers drifting helplessly so she attached a tow and took them home to Dover, whereupon the tug was immediately ordered back to Dunkirk. This tug then rescued survivors from the St Abbs, which had been bombed and sank off the French coast on 1st June. Q. How many soldiers can you fit on a tug? A. Over a hundred if they keep still for seven hours Mary Evans Picture Library

Q. How many soldiers can you fit on a tug? A. Over a hundred if they keep still for seven hours Mary Evans Picture Library

As for Albert Crossing’s SUN V, such official records as we have state that SUN V was ordered to Sheerness on 29th June under Captain W. Mastin. They were then to tow eleven cutters each manned by seven naval ratings from Dover to Dunkirk to augment the Navy crews working there. When they arrived, they had to take the 70 ratings from the boats on board the tug, and delivered them to the destination suggested by the Senior Officer aboard the tug St Clear. Afterwards, at about 11.30 at night, there was fog, but they had been ordered to show no lights whatsoever. But at 12.25am, as the fog lifted, the captain saw the huge bow wave of a warship rapidly approaching their port side. Luckily, the mate had turned the wheel hard to starboard, but the destroyer HMS Montrose nevertheless struck the SUN V, causing her to list heavily to starboard. Extensive damage had been done to the bulwarks and part of the superstructure, and she was taking in water in the port bunker. The back of the wheelhouse was leaning forward, the door on the portside having been wrenched off. She was sent back to England for emergency repairs, but it seems she returned by 1st June to assist ferrying troops to larger vessels: at the very least an eventful way to complete your apprenticeship.

In 1940, the Battle of France was lost: 68,131 French and British troops had been killed, injured or captured, but it could have been so much worse. By good fortune and extraordinary courage, the Dunkirk evacuation was an outstanding success, since over 338,000 allied troops were saved between 26th May and 4th June 1940. That was the Miracle of Dunkirk.

Alfred was then 19 years old, and never forgot his experience of the horror of war. Meanwhile, his brothers Jim, Bob and Bert joined the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) as a part-time firefighters, working on many Blitz sites in London. They recalled one such episode when, having worked a double shift without relief, they finally made it home. In those days, with no mobile phones, their parents had no idea where they were or if they were even alive. When they arrived at the front door, they were so dishevelled and smoke-blackened that their parents initially didn’t recognise them. Fighting fires in warehouses containing assorted toxic combustibles Mary Evans Picture Library

Fighting fires in warehouses containing assorted toxic combustibles Mary Evans Picture Library

But Alfred’s day-job was no less dangerous. The wide and sinuous Thames was a readily identifiable target from the air, and its banks, docks and shipping all suffered in the Blitz. Not even the humble tugs escaped: when the Deanbrook and the Lea were hit by a parachute mine at Tilbury, eleven lives were lost, as were all six of the crew of the tug Naja (left) when it took a direct hit from a V1 flying bomb next to Tower Bridge in 1944. And tugs were required not just for keeping London’s supplies moving, but were always in demand for more war-work. They were used for towing the huge concrete Mulberry Harbour sections that were built on the Thames and used off the beaches of Normandy in 1944, for example. Tug Naja destroyed by a Doodlebug, killing all onboard Mary Evans Picture Library

Tug Naja destroyed by a Doodlebug, killing all onboard Mary Evans Picture Library

SUN V survived the war and returned to civilian duties in November 1945, operating on the Thames. However, it was sold to Italy in 1966, where it was ultimately broken up in August 1980. As for Alfred Crossing, to say that he spent the war years working on a Thames tug is certainly true. But, like so many of that extraordinary generation of London’s watermen, lightermen, dockers and stevedores, it’s not the whole truth.

June 1940: Job Done. Tugboat crew, just back from Dunkirk Unknown photographer

June 1940: Job Done. Tugboat crew, just back from Dunkirk Unknown photographer

Further Reading

Atkin, R. 2020 Pillar of Fire: Dunkirk 1940

Bates, L. 1985 The Thames of Fire: the battle of London’s river 1939-1945

Demarne, C. 1991 The London Blitz: a fireman’s tale

Grehan, J. 2018 Dunkirk: nine days that saved an Army

Jupp, J. 1986 ‘Personal Reflections on London’s Lighterage Industry’, R. Carr (ed) Dockland, p177-185

Milne, G. 2020 The Thames at War

SUN TUGS http://thamestugs.co.uk/sun-tugs-[1].php

Comments powered by CComment