40 Years On: The development of the Greater London Historic Environment Record

Peter James

As many will know, the Historic Environment Records (HERs) which now serve the information needs of archaeologists, planners, and academic or amateur researchers across the UK are the successors to the ‘Sites and Monuments Records’ (SMRs) which local authorities first began to develop in the 1970s.

In 1982 plans were drawn up and the foundations were laid to create such a record for London. 2022, then, marks the 40th anniversary of the Greater London SMR/HER.

What follows is an attempt to tell the story of its beginnings and the first decade of its development, when I was personally involved. These are my own recollections, but enhanced by information received from several ex-SMR colleagues.SMRs began to be created when there was growing concern that the great growth in development activities that had begun in the 1960s had caused much damage to our heritage and was continuing to put it at risk, while planning controls provided little or inadequate protection. The ‘Rescue’ pressure group was formed in 1971 and the ‘county archaeologist’ role in most English counties was developed to help counter this threat. It was these local authority officers who began to develop SMRs as a tool, with the principal aim of helping to inform their own planning departments about the existence of historic or archaeological assets in their counties, and these records began to be computerised in the mid 70s. Archaeological units also began to spring up, one of the first being the Guildhall Museum’s (later the MoL’s) Department of Urban Archaeology (DUA), formed in 1973. The seminal work The Future of London’s Past, by Martin Biddle and Daphne Hudson, was published in the same year. However, field archaeology outside the City continued to be carried out by a patchwork of museums, 'excavation committees' and local societies until 1983 saw the creation of the Department of Greater London Archaeology (DGLA), another department of the MoL, like the DUA. (For an excellent review of the changes in planning legislation and archaeology in London over the past 50 years, and the organisations involved in it, see Hana Morel’s article in the journal The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice.

In administrative terms Greater London was very different from the counties. In 1982 it had 34 local planning authorities: 31 boroughs, the 2 cities of London and Westminster, and the London Docklands Development Corporation (a quango). It was unlikely that each of these would develop an SMR for its own area, and would no doubt have been a very inefficient way to provide a London-wide record anyway. The Greater London Council (GLC) was the only London-wide administrative body, and one of its powers was to direct local planning authorities in the granting or refusal of listed building consent. So it was that on the initiative of the GLC’s Historic Buildings Division the GLSMR was born.

The GLC’s initial requirement was for a computer-based record of Greater London’s historic buildings and structures, because it needed to have more sophisticated ways of handling the information it both used and generated in its work on historic buildings. However, the GLC was also aware that similar databases had been developed for archaeology. A GLC Historic Buildings Division officer, Daryl Fowler - an archaeologist - was the prime mover for an SMR for London and he drew into the discussions the MoL, the Passmore Edwards Museum (PEM) and the Kingston Heritage Centre (KHC). It was probably no accident that at that time senior managers in those museums were archaeologists: Max Hebditch (director) and Hugh Chapman (deputy director) at the MoL, Pat Wilkinson (curator of Archaeology & Local History) at the PEM, and Marion Hinton (curator) at the KHC. It was well understood that there was an enormous amount of archaeological work, both past and present (and growing apace) whose results needed to be systematically available to a wide range of users. Furthermore it was recognised that almost every English local authority already had or was developing a computerised sites and monuments record while London did not possess one. Another strong incentive for action in 1982 was the very real fear that the GLC would be abolished by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. It was felt that the time frame available to establish such a record London-wide might be very short.

The GLC was to provide the funding for the project and the computer system, and compilation of the data was to be carried out by staff of the Historic Buildings Division (for the built historic environment) and of the MoL and others (for the archaeology). My own involvement began when I was working for the DUA, and had recently finished writing up an excavation report. I responded to an advert for an archaeologist to carry out research for the proposed Greater London SMR, to be employed by the MoL. I was interviewed by Hugh Chapman and Harvey Sheldon (head of the new DGLA) and was offered the job, largely I think because I’d had previous experience of working on an SMR at South Yorkshire County Council. I did point out that that SMR was a very different beast from the proposed computer database for London, in that the records for South Yorkshire were stored on index cards, and interrogated by means of optical coincidence cards*, which today seems positively archaic. (*Some younger readers may need to Google that term!) However, it was enough to convince Hugh and Harvey and I began work in June 1983 tasked with conducting a survey of all the known or potential repositories of information about Greater London‘s archaeology. I was furnished with an annual London Transport ‘all zones’ travel pass to help me get around, which was invaluable because in that year I visited about two hundred institutions, both local and national, mainly museums and archaeological and historical societies. My role was to explain to these organisations what the SMR was intended to be, establish what records they held and in what form, and (crucially) whether they would be willing to co-operate with the GLSMR in providing access to those records. It was encouraging to meet with widespread support and enthusiasm for the project.

In tandem with my own research an enormous amount of other work went on in ‘83 and through ’84 to get the project to the point where data compilation could begin. The task was overseen by Nigel Clubb, who was appointed in September 1983 by the GLC Historic Buildings Division to be their project leader. In ’84 my contract was extended to lead the team of archaeological data compilers, and James Edgar was appointed to do the same for the historic buildings data compilers. (James was succeeded after a short time by Delcia Keate). At the same time the GLC engaged a programmer to develop the database. Key decisions had to be taken from the beginning: on what information was to be recorded, and on the scope and structure of the record. For example, one of the first decisions to be taken was that both historic buildings and archaeological items would be put on the same record (London was one of the first SMRs to do this). Also included would be buildings in local conservation areas, and registered parks and gardens. Careful consideration also had to be given to the level of detail that would be recorded for each item. Following a system first developed in North Yorkshire it was decided that each item record would have equal status in the database, but groups of individual records may be related to one another as primary records, component records of a primary, or sub-components. About 100 pieces of information could be recorded about each item, whether as a primary, component or sub-component record. This system afforded great flexibility, so that a single record could refer to a complex archaeological site or building (or group of buildings) at one extreme, or a single listed bollard or an archaeological stray find at the other. Decisions also had to be taken on the rules for data entry and controlled lists of terms (thesauruses) that were to be used for the structured (i.e. searchable) fields in the database (site location; period; type of artefact/building/structure; statutory status; bibliographic references; et al). The ability to include free text was also required, and the locations of items recorded on the database were to be marked by hand on film overlays attached to O.S. maps at 1:1250 scale for parts of inner London, or 1:2500 for outer London.

It was expected that the database would inevitably grow to be very large, it would need to serve a variety of customers with different interests, and it also needed to be robust and remotely accessible - by SMR staff as well as by its users. The computer system therefore had to be large and powerful. In these circumstances, and at that time, a PC-based record was not a viable option. The GLC therefore chose, not surprisingly, to use their own in-house mainframe computer at County Hall’s Central Computer Service (CCS) for the record. This had the advantages that hardware and software were already in place, communications across a wide area were well established, and the cost of developing and running the system was internal to one organisation. The database system was ‘ADABAS’, the programming language was‘NATURAL’.

It was recognised from the start that the SMR would have a very large constituency of contributors and users: the many local planning authorities, a number of professional and amateur archaeological bodies active in the field and in research, as well as many museums, and national bodies like the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments for England (RCHME) and the Historic Buildings & Monuments Commission for England (HBMCE), later branded as ‘English Heritage’. One way of making the SMR responsive to the needs of this wide constituency was to base the members of the SMR team in a number of the organisations both providing and using data. Another was the existence, from the beginning of the project, of an Advisory Group on which representatives of many organisations could monitor progress and provide an input into future policy making.

It was clear that to achieve the first objective of compiling a “basic” sites & monuments record in limited time (with the threat of the GLC’s abolition looming ever closer) considerable manpower resources would be needed, and recruitment began in late 1984. In addition to Nigel’s GLC post by early 1985 the MoL was employing eight staff, and the DUA, the PEM and KHC were employing one person each. The SMR assistant (compiler) working for Kingston Heritage Centre compiled archaeological records for Kingston Borough and South-West London; another, based at the Passmore Edwards Museum, covered the archaeology of North-East London. The compiler for the City was based in the MOL library and the one for the West London area was based in the DGLA’s office in Brentford (later at Gunnersbury Park Museum). Those compiling for North and South-East London, and myself (as archaeology team leader) were, after a short spell squatting in the MoL library, based in shared accommodation with DGLA finds staff at the old nut warehouse at Potters Fields in Southwark. Not the most comfortable workspace, especially in winter, but this was compensated for by our view, which took in both the Tower and Tower Bridge. When the warehouse was scheduled for demolition we, along with the DGLA staff, moved to Glasshill Street near Waterloo station. The team leader for historic buildings (James, then Delcia), along with two historic buildings compilers and the map co-ordinator were accommodated in the GLC’s offices at Chesham House on Regent’s Street. All the records were compiled, by hand, on printed forms which were sent to a County Hall bureau service for inputting to the computer.

By the Spring of 1985 Nigel and I were able to write in the London Archaeologist (Vol.5 No.2 ) that “Data collection has been in progress for only two months. In a project of this complexity it is inevitable that a great deal of time will be spent on induction and discussion in the early stages. Nevertheless, present indications are that the staff are tackling the work with considerable understanding and vigour, and the quantity of output so far is impressive.”

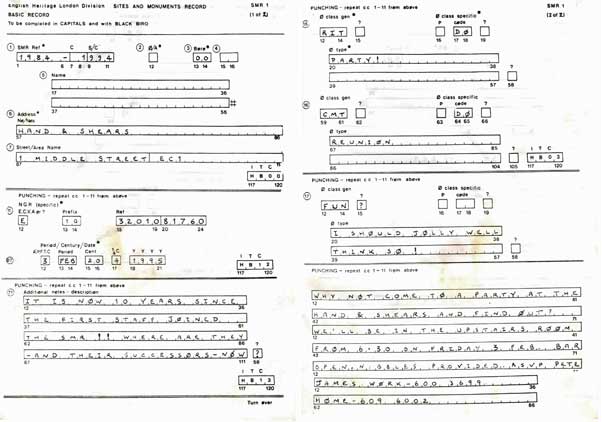

The SMR data recording sheet (here re-purposed as an anniversary party invitation in 1994)

SMR staff in some locations (MoL, Chesham House and Glasshill Street) were able to access and check the records via remote ‘dumb terminals’ - which was clearly not the best arrangement for those staff based outside central London!

Staff at Chesham House in 1985. From front to back: Val Shepherd, Zoe Croad, Delcia Keate and Nigel Clubb.

Staff at Chesham House in 1985. From front to back: Val Shepherd, Zoe Croad, Delcia Keate and Nigel Clubb.

It can be seen that the header on the data input sheet refers to “English Heritage London Division”, which dates it to 1986 or later. Earlier versions would have carried the “Greater London Council” imprint. The reason for this change was that on 31st March 1986 Margaret Thatcher’s government carried out its threat and abolished the Greater London Council. The planning advisory functions and responsibilities of the GLC Historic Buildings Division, including the SMR, passed to English Heritage (London Region). There was some resistance within English Heritage to taking on the SMR – not least to the costs of maintaining it - but the argument prevailed, largely because by his time the SMR had started to prove its worth. It held detailed information about approximately 95,000 items (at primary, component or sub-component level) and was able to supply tailored printouts and related marked-up O.S. maps to planning authorities, archaeological units and others. In a recent email exchange Robin Densem, an ex DGLA archaeologist, said “I remember your team gave us (i.e. the DGLA) the SMR printouts for the London Boroughs. I got hold of some 1:10,000 scale maps and plotted the SMR items and surface geology for Merton, Sutton and Croydon, using the printouts. Wow! This helped so much when writing letters to the local planning authorities and to developers as at that time we were unsustainably both planning archaeologist (i.e. advisor) and contractor!!”

However, there was one other major hurdle to be overcome at this watershed moment in the SMR’s history, namely, the continued provision of the computer technology and services that were critical to the record’s very existence, because the GLC’s computer services department was one of the multitude of assets the ‘London Residuary Body’ - successor to the GLC - was tasked to dispose of, and it was sold to a private company, Hoskyns plc. Happily an agreement was reached, if only for an interim solution, as was described by Hugh Jones in a paper to the Computer Applications in Archaeology conference in 1989.

Hugh, working for English Heritage, took over Nigel’s management role in late 1986. He wrote “Since abolition, English Heritage has paid for the computer service on a 'cost only' basis- that is to say that the Residuary Body only covered its costs and did not make a profit. Hoskyns (when they took over) agreed to increase their prices only by the rate of inflation for three years and to introduce profitability by cutting operating costs”.

The staffing arrangements remained unchanged after March ’86, with English Heritage now funding the MoL, DUA, Kingston Borough and the Passmore Edwards Museum to employ the personnel. However, the SMR underwent a sea-change in 1991 when it was taken in-house by English Heritage, to be an integral part of the Greater London Archaeology Advisory Service (GLAAS), which had been established in 1990. All the SMR staff employed by the external, partner organisations were made redundant, including myself, although some were able to take up other posts within EH. I joined the MoL’s curatorial department to work on collections management and information.

It is for others to take up the story of the SMR and its transformation into the current Historic Environment Record under English Heritage (Historic England from April 2014) but I will briefly say that probably the biggest milestone in its development post-1991 was the migration of the database to ORACLE, which took place in 1992. When EH took over the record in 1986 it conducted, as expected, a review of the services provided by Hoskyns plc, and of the computer system. Hugh Jones in his 1989 paper said “The disadvantages of the current computer system are now believed to outweigh the advantages. There is also a changed standpoint since the SMR has been run by English Heritage. Under the GLC, there was a need to set up a system, and get it running quickly, before abolition. Cost was perhaps not as important a consideration as it is now, as the computer service was free at the point of use.... In English Heritage, unlike the GLC, conservation is the primary function, and the organisation is already involved in a considerable way in archaeological computing, e.g. in the Central Excavation Unit and the Ancient Monuments Laboratory, as well as initiatives in SMR computing (elsewhere in England), including grant-aid”. He goes on to say that English Heritage would now look to the agreement on computing standards reached with the RCHME to guide the future development of the SMR - “The objective is therefore to develop a replacement computer system in-house for the SMR, based on the relational database ORACLE”. Hugh also noted that the system of using marked up film overlays attached to O.S. maps “is adequate for the moment, but no more, and in the medium term there will be a need to develop a new system, which it is hoped would be computerised.” He goes on to predict that “In the long term, there is no doubt that SMRs will make use of fully-fledged Geographic Information Systems, preferably in conjunction with many other categories of data, but it may be some time before such systems are fully functioning in a form which is affordable to most archaeological users”. And it so came to pass, just a few years later.

The migration to ORACLE was successfully completed in 1992, bringing the desired cost savings as well as much improved functionality, further enhanced in 1999 when GIS capabilities were added, making the GLHER the advanced, versatile system that we know today.

I cannot end without acknowledging the effort and skill of all the people who worked on or supported the development of the Greater London SMR in those early, intensive, days. They are too numerous to mention individually (at least 30 by my estimate) and in trying to do so I would inevitably leave some out. Together they built something, in limited time, that not only proved to be useful in its first incarnation but also provided a firm foundation for the future. The record has changed enormously in many ways (in look and feel, scope, accessibility, etc), but the basic primary/component/sub-component record structure has not changed since it was adopted in 1984, as I was able to see in 2014 when, for a short time, I worked on the HER with GLAAS.

My memories of those early years on the SMR include long meetings hammering out the detail of thesaurus terms or how to record addresses, and of me burning the candle at both ends to knock out the SMR Compilers’ Guide on our state-of-the-art AMSTRAD PCW word processor. I also remember how we were a close-knit group who enjoyed socialising together too. Highlights were occasional team-building days out to places of interest like Lambeth Palace, the Lloyds building, Lewes, St Albans and Fishbourne Roman Villa. Long-standing friendships were forged in those few years - and even one long-lasting marriage!

For their help in preparing this article I am indebted to the following former SMR staff members: Sue Browne, Nigel Clubb, Jonathan Colombo, Nick Davis, Debbie Edwards (née Walker), Hugh Jones, John Lewis, Catherine Lewis (née Rogers), Andrea Sinclair, Debbie Walker, and Barbara Wood. Also my thanks to Robin Densem for sharing his memories of using the SMR.

Did you work on, or were involved with, the SMR between 1982 and 1991? If so please share your memories, photos or other memorabilia from that time. We would love to hear from you!

Peter James, March 2022

To download a pdf copy of this article click here

Comments powered by CComment